Fisher – Transform Issue 1 pdf

Sarah Fisher

Sage Gateshead

Abstract

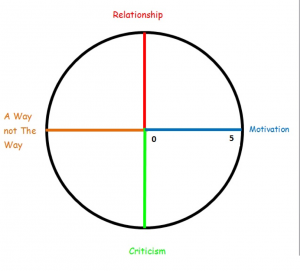

In this paper, I explore the impact of an andragogical approach, which was developed through undergraduate autoethnography, upon participants in the Music Spark project at Sage Gateshead, as well as on my ongoing development. Using Participatory Action Research methods, I led a collaborative enquiry into the experiences of learners and myself as fellow musicians involved in practical music making. From facilitating participants’ learning through to supporting their own delivery, there are elements of my approach which have proved beneficial with the participants’ development as practitioners in their own right. I discuss a number of findings, including the value of reflection as a tool for learning, and the relevance for other learners of the four ‘pillars’ of my ‘A Way, Not The Way’ philosophy: the relationship between teacher and student; motivation; constructive criticism of musicality, not of disability; and the development of a way, not the way to teach / learn new musical skills.

Introduction

Autoethnography:

In my undergraduate studies I developed a pedagogical approach; called ‘A way not The way’, through an autoethnography, which is:

The use of personal experience and personal writing to (1) purposefully comment on/critique cultural practices; (2) make contributions to existing research; (3) embrace vulnerability with purpose; and (4) create a reciprocal relationship with audiences in order to compel a response (Denzin, 2014, p. 20).

An autoethnographic approach enabled me to gain a deeper understanding of the different aspects of pedagogy which benefited my own development. I used these reflections to infer possible benefits for the learning of other disabled people. It allowed me to use qualitative research to explore how my personal experience of learning music helped develop my understanding of my disability, and enabled me to develop an approach to teach other disabled people.

Andragogy

As well as an autoethnographic approach, this paper also sits within an andragogical context, which could broadly be described as ‘adult learning’. Andragogy has an emphasis on a self-directed approach and students take responsibility for their own decisions and learning. Within this research project, students reflected on their teaching approach and found ways to fulfil the intended task and improve their practice along the way, developing their own unique way of delivering activities which they can use to teach others too.

Music Spark

Through my professional work post-graduation, I have implemented my approach in practice, especially in my work with Sage Gateshead’s Music Spark Programme. This is a community music training programme for young people and adults with varying learning disabilities, combining music making and song writing, as well as developing their practice to lead sessions and become music practitioners. As a Project Musician, my musicianship skills help the participants learn new or develop pre-existing instrumental skills. My leadership skills help them see new approaches they can utilise when leading their own activities.

Within the UK, 19% of the population have a disability; ‘according to figures from the department for Education, less than 1% of the teaching workforce has a disability’ (Lepkowska, 2012). Disability should not be a barrier for achieving ambitions; Music Spark helps to give the participants the skills needed to work as practitioners. Participants in Music Spark begin as Trainees and learn skills to deliver music activities. At the end of the year, Trainees deliver a workshop. They then progress to Advanced Trainees and develop skills in supporting the new Trainees to lead activities. Advanced Trainees then become Volunteers who deliver and support the training of Advanced Trainees.

In this paper I intend to focus on the benefits and challenges I have seen of, ‘A way not The way’, in practice throughout the year. It is built up of four different parts: relationship, motivation, constructive criticism of musicality, not of disability; and the development of a way, not the way to teach /learn new musical skills.

Relationship

Before any musical ability is developed it is important to form a relationship between the participants and the Project Musicians, built on trust and understanding. Developing a comfortable setting allows people to speak up and understand more about each other, allowing better communication between teacher and student. Within critical pedagogy Freire states it is a two way process:

Through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers. The teacher is no longer merely the one-who-teaches but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a process in which all grow’ (Freire, 1996, p. 16).

The roles become interchangeable; the teacher teaches the musical skills, but the student teaches them how they can play their instruments based on their particular needs, making it easier for the teacher to tailor further activities appropriately. This could be linked to the pedagogical approach known as andragogy, where: ‘though the destination may be decided by the tutor, the route involves greater learner involvement, acknowledging the importance of relevance, motivation and problem-solving’ (Price, 2013, p. 193).

As the teacher-student relationship grows, a mutual development of agency begins to develop: ‘to engage in a culture of questioning that demands far more than competency in rote learning and the application of acquired skills’ (Giroux, 2010). The student’s agency develops; the teacher gains more of an understanding of the specific learning needs of an individual but also around disability in general, therefore developing confidence and capacity which can be applied in similar situations.

Relationship needs to be built around trust: ‘establishing trust takes time, but this is what usually provides a student with the foundation to take risks in their development, have the confidence to move out of their comfort zone, and so reach new levels of achievement’ (Hallam & Gaunt, 2012, p. 82). Once trust and confidence have been established, musical learning can begin; students are in an environment where they feel safe to speak up about their challenges. As Dan Siegel states, when our ‘threat-assessment system’ (Siegel, 2011, p. 126) lets us know we are safe, our bodies relax and our minds become more clear and focused. As time goes on within this ‘safe’ environment, the students musical skills develop, their arousal levels become optimised and they can play/learn effectively:

Level of arousal is related to motivation in a particular way. If a student is under-aroused, for example, then he will feel apathetic or bored and will not perform well. On the other hand, over-arousal leads to stress and anxiety, and this can lead to loss of motivation. This means that there is an optimal level of arousal at which the individual is at his or her peak of motivation and performance. (Legge & Harai, 2000, p. 22)

This optimal level of arousal can be defined as being in the state of ‘Flow’, (Csikszentmihalyi, 2009) in which the individual is fully immersed and their full focus is on the activity resulting in enjoyment throughout the activity.

Motivation

Once the relationship is formed, motivation can follow. Having less pressure means the students can meet an optimal arousal level. A positive setting makes it more comfortable for students to try new things leading to their musicianship developing. This may be for various reasons, including the idea that music may be an escape for them from feeling disabled. ‘When music becomes involved, the presence of disabilities seems to fade or disappear entirely’ (Weiss, 2009), which in turn can be similar to being in the state of ‘flow’. This escape can also lead to being more motivated, which can be described as intrinsic motivation: ‘when he or she undertakes an activity which is enjoyed and valued for its own sake’ (Hallam & Gaunt, 2012, p. 60).

Developing musical skills and having a positive motivational attitude can lead to the student gaining more confidence and others becoming aware of this development. For example, the students may receive praise and encouragement for their progress. This links to extrinsic motivation which ‘occurs when an activity is valued for the rewards it will bring’ (Hallam & Gaunt, 2012, p. 60).

Constructive Criticism

To develop as a musician/practitioner it is important to get constructive criticism. This is no different for disabled people. However, it is important to only criticise the musicality and not the disability. This is only accomplished with the relationship being built on trust, understanding and empathy between the teacher and student. Together they build on their knowledge of what is achievable. If the teacher has an understanding of the student’s needs and abilities the teacher can push the student to their full potential, without overdoing it, causing injury or low self-esteem, whilst at the same time developing musical skills.

A Way not The Way

The last element is to develop ‘A’ way to learn and play new things, not necessarily ‘The’ way. Everybody learns differently and for those who have disabilities, some things may need to be adapted to find ‘A’ way to play. Rather than a more traditional ‘pedagogy’ focusing on one, specific teacher-directed way of learning, ‘A’ way can be found through an andragogical approach, where both teacher and student develop ways to learn. Between them, the outcome is the same; they just need to find ‘A’ way to achieve it based on their ability and considering the challenges they may face.

Methodology:

By using participatory action research (PAR) methods I discovered a deeper understanding of the ways in which the four pillars of my approach helped the participants – and my own – practise as musicians with disabilities, and how it may influence us in our future practice.

PAR is described as a ‘communicative approach’ (Stige, Andsell, Elefant and Pavlicevic, 2010). Everyone works together to identify problems and suggest solutions. Over the course of the process, these suggestions are put into practice and then evaluated for the next round of reflections and practice.

Using PAR methods as the basis of my research benefited both the participants within their practice as well as myself – the researcher. PAR allows participants to ‘speak their truths’ (McIntyre, 2008, p.12)and be given a comfortable space to do so. As all the participants and I have disabilities, I wanted to be able to share our thoughts, which could in turn make a change to how other people understand us. PAR ‘is about giving marginalized people voice and about listening to the voices of others’ (Stige, Ansdell, Elefant, & Pavlicevic, 2010). This can relate to the social model of disability: ‘the root of disability oppression lies far more in its socialization than in embodied impairment’ (Lubet, 2011, p. 4). Therefore giving disabled people a space and a voice can allow them to make a change within society benefiting themselves and others.

Having worked on Music Spark for the past three years, I have built a strong relationship with the participants through being open about my disability. This helps participants to be open about their thoughts around the approach, and their own challenges and to not see them negatively. Within the safe environment of sessions we focus on ways to overcome our challenges and on our abilities through dialogue. As McIntyre states; ‘it is my belief that practitioners of PAR must take the first step in openly addressing the ethical challenges that occur in PAR projects’ (McIntyre, 2008, p. 12).

Method

Using a reflection diary over the year allowed me to see the different elements of my approach in use from my perspective as the teacher (see Appendix 8). Whilst my reflection diaries were collated over the whole year, this action research project, involving nine participants, was conducted over one month during weekly sessions. Time was set aside for the presentation, data collection activities and reflections each week.

I outlined that I required the participants’ help in collecting data and emphasised that we would all be working together to do so. It ‘requires a deep commitment by researchers and participants to work together to provide equity, safety and parity in resources within the PAR process’ (McIntyre, 2008, p.13). Combining this research into the weekly activities allowed me to have informed consent as it was part of the overall project run at Sage Gateshead. The data was collated anonymously ensuring confidentiality.

Due to the nature of the participants’ disabilities I tailored the activities and presentation to suit their needs. In the first session of the research project I delivered a presentation, I made this as engaging as possible in order to avoid losing focus and to make it understandable (see Appendix 1). It was important that ‘the language used in the research project [was] understood by participants’ (McIntyre, 2008, p. 12). Therefore I broke it down by having discussions and activities throughout the presentation, including the importance of each element within our practice (see Appendix 2) and what makes a good practitioner (see Appendix 3).

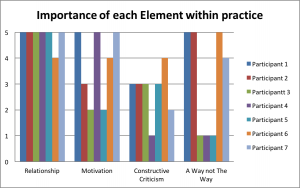

The participants then led a workshop in a school to deliver the activities they had learnt over the year. For the reflection activities, I designed a Socratic Wheel (see appendix 4). Using a Socratic Wheel allows for ‘a self-assessment process later integrated into formal monitoring and evaluation plans’ (Chevalier & Buckles, 2013, p. 124). The scale was between 0 – 5. They measured the importance of each element in their practice, followed by a reflection activity where they were asked to say ‘what went well’ and ‘even better if’ by completing the respective sentences (see Appendix 5). Rather than reflecting on negative experiences, framing feedback in this positive way was inspired by Carol Dweck’s idea of ‘growth mindset’ where abilities can be continuously developed without a negative impact: ‘giving feedback in a way that promotes learning and future success’ (Dweck, 2017, p. 141), and consistent with the approaches of other practitioners within Sage Gateshead’s participatory ‘community of practice’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1999).

Findings

Throughout this project I found participants had an understanding of each of the four elements. As the participants stated during the presentation activity, the relationship allowed them to ‘build bonds’ and develop ‘teamwork’. Motivation ‘helps us know we are doing the right thing’; they know that getting criticism helps everyone ‘understand them’, and that ‘A way not The way’ ‘depends on the group’ (see Appendix 2). Although the participants may not be able to distinguish the link between them, they can see the relevance and importance of the four elements within their leadership.

The results from the Socratic wheels show that the majority of participants believe that having a dialogic and supportive relationship between everyone is important within sessions. The relationship element was marked at the highest by the majority of the participants (see Appendix 6). However, there are conflicting results from the other elements, especially ‘A way not The way’. Participants marked it either very high on the Socratic wheel or at the very bottom, suggesting it is either very important or not at all important (see Appendix 6).

Participants’ reflection on their practice and experience over the year (see Appendix 8) has shown they can identify how their practice can be improved. Participants developed ‘A’ way to deliver an activity which suits them. As stated in my reflection diary, ‘for example, a Trainee may watch an Advanced Trainee, Volunteer or Project Musician lead an activity. When their turn for delivery comes up they may recall the activity step by step fluently with little prompting. However, another Trainee may lead the same activity but needs prompting throughout each step of the activity, for example; using flash cards to remind them’ (see Appendix 7).

Receiving feedback and observing others’ leadership helped their development. One participant developed his eye contact in sessions over time due to reflecting on this as a whole group. As stated in my reflection diary, ’It was important that we didn’t criticise it outright but worked on the relationship which allows the participant to reach his full potential as a practitioner step by step’ (see Appendix 7, p.3).

Doing these reflections and discussing our weekly sessions has helped us Project Musicians to develop our practice. We can focus on the participants abilities and what motivates them to improve their musicianship and leadership; such as developing their confidence, and building their repertoire (see Appendix 8).

Discussion

This research has shown that reflecting on one’s practice helped the participants of this study to develop as practitioners. It allowed participants to understand more about the way they deliver sessions, how to reflect more and what makes a good practitioner. I developed my practice and expanded my knowledge around my pedagogical approach with relevance to how it can be adapted and used in the wider society of community music.

The results from the Socratic wheels confirmed what I initially outlined in my approach: that having a relationship of trust and understanding is the most important part. The majority of participants rated that at the highest scale, which also links with what the participants suggested as to why the relationship is an important element in being a practitioner (see Appendix 2).

From my observations of the four elements within my work on Music Spark, I have seen the impact it had (see Appendix 7). ‘A way not The way’ can be linked with the importance of the relationship, which is followed by motivation. As project musicians we understand the participants’ needs more and can tailor activities appropriately. Having that relationship, knowing why they act the way they do, helps us to build trust and understanding and allows us to motivate them without overdoing it. This can link with the REACH framework which is defined as Relationships, Effort, Aspirations, Cognition and Heart and is designed to help students reach their full potential and gain skills needed to succeed in school and life. ‘A way not The way’ has some common themes with this approach especially the ‘E’ part of the framework which is defined as:

‘Effort: Adults also need to help students believe that when they challenge themselves mentally, use good learning strategies, and see mistakes and failures as opportunities to improve, they can become smarter and more successful’ (Search Institute, n.d.).

Despite some clear results, I have to take into account the participants’ learning disabilities. Due to the nature of their disabilities, not every element I spoke about within my presentation was comprehended by the participants. They were unclear as to what to do or what each activity meant during some sections, so the activities were broken down even further into steps and one-to-one conversations to discuss the elements helped to describe each part.

Although I tried to make this as inclusive as possible, there were some challenges. The concept of ‘A way not The way’ proved hard for some of the participants to understand, especially those on the autistic spectrum. From my observations I found they were only able to see one way of leading; although adapted to suit their ability, they would class it as ‘the’ way and this being the only way they lead. I believe this is why I received conflicting results for the ‘A way not The way’ importance section.

Conclusion

Originally, this approach was based around autoethnography and on my personal development as a musician learning to play music and deliver sessions. Therefore, this could be interpreted as being subjective; however, it also has some level of ‘ecological validity’ i.e. ‘giving an accurate portrayal of the realities of a social situation in its own terms’ (Cohen et al., 2011, p. 195).

However, throughout my work with Music Spark I have seen the approach being adapted to the needs and abilities of the participants. The elements which make up the pedagogy can be tailored to suit the individual, meeting their needs and making adaptions for them within this approach, therefore making it more valid and reliable for the individual and the experiences it brings about (see Appendix 7).

Both participants and project musicians widened their practice through using different approaches. The space during the sessions created an ever-changing environment as we adapted to suit people’s needs that changed each week. This helped keep sessions engaging, with everyone learning new things and making adaptions which in turn led to sessions becoming more inclusive for all (see Appendix 7).

However, this research was completed using a small number of participants – nine in total. It is not a general theory to be used in everyday practice. There are also some ethical issues due to the participant’s disabilities; it proved to be a complex model to understand. They understood the four elements, but found it conceptually tricky to see the connection between them.

Throughout this research, participants have been able to use this approach as a reflective tool; it allowed them to identify the importance of the approach, especially the relationship part. This approach was originally based around working with other people with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEN/D). However, there are other effective theories that can be applied to teaching people with disabilities which haven’t focussed specifically on SEN/D. For example, the REACH framework by The Search Institute states: ‘The single most powerful thing that educators can do to increase motivation is to build close connections with their students’ (Search Institute, n.d.). An andragogical approach can help both the teacher and student to develop their learning:

Education is not just about the transmission of knowledge, skills, and values, but is concerned with the individuality, subjectivity, or personhood of the student, with their “coming into the world” as unique, singular being. (Biesta, 2015, p. 27)

Using the ‘A way not The way’ approach has allowed each person to find ‘A’ way to develop their leadership skills and make activities inclusive for all participants. Despite there being some limitations in understanding the concept, as practitioners we have all enhanced our practice which we can continue to develop over time.

References

Biesta, G. J. J. (2015). Beyond learning: democratic education for a human future. London: Routledge.

Chevalier, J. M., & Buckles, D. (2013). Participatory action research: theory and methods for engaged inquiry. New York: Routledge.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education. New York: Routledge.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperCollins.

Denzin, N. K. (2014). Interpretive autoethnography. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Dweck, C. (2017). Mindset: changing the way you think to fulfil your potential. London: Robinson.

Freire, P. (1996). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

Giroux. (2010). Lessons to be learned from Paulo Freire as education is being taken over by the mega rich. Retrieved 11 April 2015, from http://truth-out.org/archive/component/k2/item/93016:lessons-to-be-learned-from-paulo-freire-as-education-is-being-taken-over-by-the-mega-rich

Hallam, S., & Gaunt, H. (2012). Preparing for success a practical guide for young musicians. London: Institute of Education.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Legge, K., & Harari, P. (2000). Psychology and education. Harlow: Heinemann.

Lepkowska, D. (2012, November 12). Where are the disabled teachers? The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/education/2012/nov/12/disabled-not-encouraged-teacher-training-costs

Lubet, A. (2011). Music, disability, and society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

McIntyre, A. (2008). Participatory action research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Price, D. (2013). Open: how we’ll work, live and learn in the future. London: Crux.

Search Institute. (n.d.). The social-emotional factors that impact student motivation | www.search-institute.org. Retrieved 9 December 2017, from http://www.search-institute.org/social-emotional-factors-impact-student-motivation

Siegel, D. (2011). Mindsight transform your brain with the science of kindness. New York: Oneworld Publications.

Stige. (2016). Participatory action research in music therapy research. Gilsum, NH, United States: Barcelona Publishers.

Stige, B., Ansdell, G., Elefant, C., & Pavlicevic, M. (2010). Where music helps: community music therapy in action and reflection. Farnham: Ashgate.

Weiss. (2009). Music therapy for people with disabilities. Retrieved 8 December 2017, from https://www.disabled-world.com/medical/rehabilitation/therapy/music.php

Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of practice: learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix 1:

https://prezi.com/urtowj13gxd6/how-does-the-a-way-not-the-way-approach-influence-or-affect-us/

Appendix 2:

During the presentation as a group they discussed why each element is important when being a practitioner.

| Importance of each element | ||

| Relationship:

o Build bond o Understand them o Teamwork o Trust yourself o Supports peers for better sessions o Sense of humour

|

Motivation:

o More comfortable – used to it o Getting encouragement o Helps us to know what to do o Helps us know we’re doing the right thing o More meaning o Confidence boost

|

|

| Criticism:

o Helps understand o Wrong to criticise disability |

A way not The way:

o Depends on group |

|

Appendix 3:

The elements the participants discussed as to what makes a good practitioner are shown below (Fig.2)

| What makes a good practitioner? |

| Good communication |

| Patience |

| Plan for session |

| Confidence in yourself |

| Confidence in others |

| Taking part |

| Give time for others to think |

| Positive attitude |

| No bad language |

| Good understanding of session |

Appendix 4:

Socratic wheel

Appendix 5:

Reflection sheet, participants complete the following sentences:

Appendix 6:

Results from Socratic wheel

The data for each participant’s Socratic wheel is shown below (Fig 3). These results show that the majority of the participants believe that having a relationship is important when facilitating sessions. There is a conflicting results from the other elements, especially A way not The way, participants suggest its either very important or not at all important.

Fig 3: Results from Socratic wheel

Appendix 7:

Reflection Diary:

- One participant in particular has emotional difficulties. As a coping mechanism within sessions she has her phone out and music playing almost constantly. Throughout the day, her emotions can fluctuate and so we have to be aware of how much we push this participant to join in and lead and put her phone away for it. This has taken time for her to open up about the reasons she relies on her phone during sessions and why she leaves the session at certain times.

However, when the moment is right and the participant is leading, her leadership skills are very good, she doesn’t need to rely on the comfort blanket of her phone or music and there is no sign of anxiety, especially during activities she is well accustomed to, linking to being in a state of ‘flow’.

- Each member of Music Spark has a disability which varies for each individual. When leading an activity, although the activity is the same, the approach to delivering it differs for each individual and their ability.

For example, a Trainee may watch an Advanced Trainee, Volunteer or Project Musician leads an activity. When their turn for delivery comes up they may recall the activity step by step fluently with little prompting. However, another Trainee may lead the same activity but needs prompting throughout each step of the activity. For example, with the use of flash cards to remind them. This can link to differentiated learning; ‘the differences in students are significant enough to make a major impact on what students need to learn, the pace at which they need to learn it, and the support they need from teachers and others to learn it well.”(Tomlinson, 2000)

This in turn links to ‘A way not The way…’ as each individual has their own way; ‘A Way’ of leading the activity, not necessarily ‘The Way’. We adapt the activity to their ability and find ‘A’ way for them to deliver what is required. The outcome of the activity is the same but how we get there is up to us, as Project Musicians we help the Trainees find ‘A’ way to deliver, and the Trainees use their ability to help us find ‘A’ way. Given time and space over the sessions and building on the relationship between us, we are able to find ‘A’ way. This can link to Paulo Freire’s dialogic approach to teaching which states that,

‘through dialogue, the teacher-of-the-students and the students-of-the-teacher cease to

exist and a new term emerges: teacher-student with student-teachers. The teacher is no

longer merely the one-who-teaches but one who is himself taught in dialogue with the students, who in turn while being taught also teach. They become jointly responsible for a

process in which all grow.’(Freire 1970) Throughout the sessions we learn off each other. As Project Musicians it helps us widen our practice knowledge, as we develop more inclusive ways to deliver activities and help teach more practitioners to teach.

- As practitioners in any field, it’s important to get constructive criticism on our leadership as it can help us to develop our practice. This is no difference with CMS sessions, once a participant has led an activity, as a group we give feedback and reflect on their leadership. This links to the ‘criticise the musicality, not the disability’ part of my pedagogical approach. It’s important to only criticise their musical leadership and not their disability. This can only be done when there is a relationship of trust and understanding between all participants and leaders.

For example, one Advanced Trainee during leading constantly stares at a Project Musician whilst delivering the activity as a coping mechanism and for reassurance. As the participant has become more familiar with this activity we have started to gently mention about using eye contact with all the participants not just on one leader. We did this by discussing the importance of eye contact as a whole group and not singling anyone out. We then gave slight reminders during his activity leading to develop his eye contact. Over the weeks we have seen a small improvement. It was important that we didn’t criticise it outright but worked on the relationship which allows the participant to reach his full potential as a practitioner step by step. rew

- One participant plays drums and has autism. In every session he sits behind the drum kit as he is more comfortable there, we make sure to include the drum kit into the semi-circle we have set up for sessions. When we do games that require all of us to be in a circle, such as ‘Anyone Who/The Sun Shines On’ we move the drum stool into the circle so he can participate as best as possible with feeling in his safe zone near the drum kit. Within sessions as project musicians we make sure that we include playing a song at some point which allows this participant to play drums along to and helps him stay calmer and more focused within the sessions.

- Within sessions each week, project musicians lead different activities, from percussion, to songwriting, signing, singing and other instrumental activities. This allows the participants to see different areas of leading and also allows project musicians to develop their practice and try new activities each week. Each activity is tailored before the session to be appropriate but also during the session it may need to be adapted more to fit the participants needs. I.e. more repetition of parts so they can remember it.

As the participants see an example being led by a project musician they can then take that activity and make it their own, they learn how to lead it in ‘A’ way that suits them, therefore both PM and participants benefit from this approach to leading.

Appendix 8:

| Participant: | What went well… | Even better if… |

| 1 | Alligator Jaws, everyone did what I said, everything | I wasn’t as nervous |

| 2 | The boost in my confidence and the music spark show | I work on my leadership skills |

| 3 | I lead a game called Anyone Who, it was good because everyone joined in | If I had more experience leading other games

|

| 4 | The sun shines on when I was working with Percy Hedley | I could lengthen the game |

| 5 | Doing the warm up before singing. Joining in with the singing | Not make it too short |

| 6 | Doing the music spark show

|

I had performed to the school choir including the parents and carers on a DJ booth |

| 7 | Playing songs with the group on drums, the metro song, I enjoyed recording the metro | More drumming, I could get better at videoing the metro, I am going to miss all my friends at sage |

| 8 | Helping other advanced trainees and trainees lead their activities in the workshops and encouragement to people during the music spark show | I stayed awake and to not nod off to sleep during the music spark sessions |

| 9 | Leading vocal warm up was fun and enjoyable.

Leading at Beacon Hill. Singing and performing was fun it gave me more confidence and experience |

I could improve my vocal warm up with different actions. I can improve my singing abilities to add new skills to work on. |