Steers, E. (2021) Transform-Download PDF

Wilfrid Laurier University

Stee2790@mylaurier.ca

Abstract

The benefits of participating in community singing groups are well documented, and new research in the field has wide ranging implications for a number of positive physical, social, and mental health outcomes. Furthermore, there are many community singing groups that serve particular marginalized populations. How do these health outcomes change or differ when the choral community is not only based on musical affinity, but shared identity and experiences of oppression? This research looks at the history of thec queer choral movement and seeks to examine the impacts of participating in an LGBTQ+ community choir both on the choir’s membership and on the wider community. Using a mixed methods grounded theory approach, I developed a theory of queer choral musicking, which models the unique space created by a queer choir and transformative power this can have in a community.

Keywords

LGBTQ, queer, choir, musicking, grounded theory

Introduction

The tangible benefits to community group singing are well documented. Both anecdotal evidence and a growing body of research is demonstrating that participation in community choirs and similar ensembles is shown to have positive impacts on psychological wellbeing (Judd & Pooley, 2014), fighting back against loneliness and increasing social connectivity (Willingham, 2005), as well as improving mood, stress, and even physiological phenomena such as breathing and short-term immune responses (Glick, 2011). With the proliferation of research surrounding the benefits to community singing more broadly, there is a need to examine the impacts of group singing, in the context of choirs created as a space for marginalized peoples. There has been some phenomenal scholarship about LGBTQ+ choirs, such as the research of Dr. Frances Bird (2017) and Dr Jules Balén (2017), but there is a lack of scholarly research about LGBTQ+ choirs in Canada. This research examines the social effects of singing in an LGBTQ+ choir, the kind of community that this creates, and the impact that it has on the wider community in which it is situated. This study was done in partnership with the Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington, situated in Guelph, Ontario, exploring these questions of relationship and identity.

A note on language: I am sensitive to the fact that some members of the choral movement and LGBTQ+ community might find the term queer offensive given its history as a slur. However, I have chosen to use it, as Dr. Jules Balén does in zir book ‘A Queerly Joyful Noise’ (2017) because it has gained a more popular and common usage in recent years and is recognized as an umbrella term for LGBTQ+ identity. Queer also serves a dual purpose between noun and verb: it refers to both a particular group of people who resist or reject dominant heteronormative sex, gender, or sexualities, and to the act of queering. To queer something is to question its normalcy by problematizing its apparent neutrality or objectivity (Manning, 2015). Thus, ‘queer’ resists becoming an easily assimilated, static identity, and keeps open more possibilities for ways of being human. (Balén, 2017).

Queer History in Canada and the United States

Queer choral musicking has been a powerful site of organizing, mobilizing, visibility, and community for many decades, (Bird, 2017) and it is no coincidence that queer choral musicking emerged alongside the newfound prominence of the gay liberation movement. After the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York, there emerged a powerful, militant gay liberation movement that demanded recognition, an end to the criminalization and marginalization of diverse gender and sexual identities, and a re-imagining of the role gender and sexuality plays in our culture (Glatter, 2016). Drawing from the civil rights movement and the feminist liberation movements, these activists fought back against the aggressive policing and suppression of queer people, and for the right to live as their full authentic selves. People pushed back against the restrictive heteronormative1 perceptions of appropriate expression and relationships. In that same year, the Canadian government decriminalized homosexual acts between consenting adults, with then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau declaring ‘the state has no business in the bedrooms of the nation’ (Canadian Queer History Timeline, 2018). However, that decriminalization did not result in any significant material change in the treatment and status of queer people and queer communities.

Forming affinity and activist groups based on shared queer identity presented particular challenges because queerness is often very isolating. Other activist communities (such as the labour movement of the 19th and 20th century, and the civil rights movement in the latter 20th century) relied on community hubs such as the workplace, churches, community centers, and kinship ties to build up an active base from which to mobilize (Balén, 2017). Conversely, it is entirely possible for a queer person to be the only queer person in their family or social circle, and may potentially face rejection, ostracization, and violence from within their communities. Thus, finding connection with others who share a similar experience of marginalization can be immensely difficult. Unlike in the labour movements and civil rights movements, there was no pre-established community network of people with a shared identity, and thus the first step towards organizing must be finding people who share that identity. Finding community is rendered even more challenging, as queer people growing up in homophobic and transphobic cultures often stay ‘in the closet’. It can be immensely difficult, not to mention traumatic, to live openly as a queer person, because of the stigma and violence enacted by heteronormative society. Many queer people internalize this shame and self-hatred, and queer people of all identities have been shown to have higher rates of loneliness, depression, and social anxiety (Hobbes, 2017). Finding queer communities and connecting with other queer people thus becomes a stigmatized, dangerous, and difficult task.

Historically, a popular site for community connection is gay and lesbian bars, and bathhouses. These are places where queer people can socialize, spend time together, have fun, and engage in sexual activity, without the judgement and oppression of heterosexist society weighing on them. Unfortunately, these community hubs were often targeted by police raids and civilian mobs, with some noted establishments even being firebombed. (History of Canadian Pride | QueerEvents.Ca, n.d.) For the many who could not be fully out in their public lives or were still closeted, these stings and raids presented the danger of being deliberately outed, potentially losing access to housing and employment, and being cut off from their families. Additionally, having communities based in bars and clubs often means that social space is intimately connected with substance use. While substance use is not inherently an issue, the social stigma of queerness, and the years of abuse and rejection many queer people face, means that queer people as a whole are more at risk of alcoholism and addiction, and are more likely to engage in riskier forms of sexual intimacy (Hobbes, 2017; Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008). Finding community spaces that are accessible, for people of all ages, for recovering addicts and for disabled people, becomes a crucial, yet nigh impossible task.

Being out, and being proud, and finding community was a political statement. Many queer activist organizations formed to fight back against police brutality and fight for legal protections for gender and sexual diversity, as well as creating more inclusive community hubs to connect and network with other queer people. Organizations included ASK in Vancouver, Queer Ontario, The University of Toronto Homophile Association (UTHA), the Lesbian Organization of Toronto (LOOT) and many others. Queer publications also started gaining prominence, particularly the Pink Triangle Press (Canadian Queer History Timeline, 2018).2

This communal organizing took on an unprecedented urgency in the early 1980s, when the AIDS pandemic (then known as GRID, or ‘gay-related immunodeficiency’) began devastating the queer community (Altman, 1982). The disease was met with fear, dismissal, and ridicule by the mainstream culture, with many homophobic religious leaders and politicians describing it as ‘divine punishment’ for the sin of homosexuality (Scherschligt, 2017). The apathy and ignorance of most national public health organizations meant that it became necessary for queer communities to bond together to care for and support one another, because no one else would. Many prominent organizations arose during this immensely difficult time, including ACT UP (AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power) in the US and AAN (AIDS Action Now!) in Canada (Thirty Years of HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of an Epidemic, n.d.). Many cities had independent AIDS committees dedicated to supporting local community members and advocating for healthcare access. It was in this context of tragedy and activism that the queer choral movement was born.

Queer Choral History

Historically, collective music making has been an integral part of any social movement. Rosenthal and Flacks (2016), in their seminal book Playing for Change: Music and musicians in the service of social movements, identify the four major roles of music in activism:

1. Serving the committed,

2. Educating listeners about the cause,

3. Converting more people to the movement,

4. Mobilizing the membership.

We can see these active musical roles played out in many historical social movements, including the global labour movements of the 19th and 20th centuries, the civil rights movement in the United States (Balén, 2017), and the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa (Byerly, 2013). Queer collective music-making serves an additional purpose: it provided an intergenerational community hub and social connection for people of diverse backgrounds and identities. As mentioned previously, queer communities had few pre-established communal hubs through which to connect and organize, unlike the union assemblies of the labor movement or the historically African-American churches. Queer choirs emerged within a decade of the spark of Stonewall, and quickly spread all over the world as a space for queer people to find one another, connect, and celebrate their identity and their community without fear or judgement.

One of the first choirs in the queer choral movement is the Anna Crusis Women’s Choir, formed in Minnesota back in 1975. Many queer organizations, particularly lesbian organizations, emerged from feminist circles and were informed by generations of feminist activism (Balén, 2017). Anna Crusis’ music-making is intensely communal and committed to a politic of inclusive social justice, and they prioritize community formation over performance and prestige (ANNA Crusis Womens Choir, n.d.).

The San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus (SFGMC) is one of the most famous queer choirs. It was formed in 1978 and was the first to use the word “gay” in its name. SFGMC quickly made a name for themselves: their first public performance was at a candlelight vigil after the murder of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician in the USA. They sang Mendelssohn’s hymn “Thou, Lord our Refuge” on the steps of City Hall, and from that day onwards has continued to showcase queer excellence and artistry (Our Story | SFGMC, n.d.). Though they initially faced a lot of hostility, they have been instrumental in pushing the choral mainstream into imagining more possibilities for the social and political roles choral music can play (G. Yun, personal communication, September 28, 2020). They also inspired the formation of dozens of other gay men’s choruses across the US and around the world after their 1981 tour, even in countries where being gay was a criminal offence.

Larger organizations, such as GALA Choruses (Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses) and LEGATO, the European association of LGBTQ+ Choruses, began connecting choirs all over the world and hosting major events with thousands of people in attendance. The first of these events was ‘COAST’ (Come Out and Sing Together!) in 1983, and has been hosted every four years since (History | Gala Choruses, n.d.).

Today, GALA has over 190 registered member choruses all over the world (GALA History, 2011), and LEGATO has 120 member choirs across 20 different countries (Home | LEGATO European Association of LGBTQ+ Choirs, n.d.). In Canada, there are 27 choirs registered under the GALA umbrella, from the small lesbian acapella group The Women Next Door in Halifax, to the massive Vancouver Men’s Chorus, to the group in this study, the Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington.

These choirs took on an enormously important role with the emergence of the AIDS crisis. Queer choirs soon became some of the only social spaces people with HIV/AIDS could openly participate in, because of the stigma associated with the disease. Choristers supported one another and fundraised to help get what treatment was available, supported partners as needed, and sang at each other’s funerals. Such was the devastation of HIV/AIDS, some choristers remember singing at ‘one funeral every weekend’. To this day, SFGMC maintains a “fifth section” in all of its concert programs, commemorating the over 200 members who have lost their life to AIDS (Our Story | SFGMC, n.d.). It is difficult to overstate how crucial these community spaces were and continue to be.

The Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington

The Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington was formed amidst the devastation of AIDS and the swelling gay liberation movement. Robert Booth founded the choir in 1993, alongside his partner, who was an active choral singer. This was a time when, to quote Booth, ‘outside of Toronto, there was absolutely nothing other than funerals and the AIDS committee that was sort of any kind of hub for the queer community’ (R. Booth, Personal Communication, August 14, 2020). For those living in more rural parts of the country, there was little respite from the horror of the AIDS crisis and the rampant, normalized homophobia in all aspects of life. Thus, the choir was created as a site of joy, a place where you could go to celebrate queerness and be out with people who would support and understand you. Beginning with their first performance at the annual AIDS walk in 1994, the choir has grown and expanded into becoming an influential voice in the local queer community and choral community. Even though the majority of queer choirs are single-gender spaces (gay men’s choirs, or women’s choirs), the Rainbow Chorus has been an all-gender choir since its inception and has always sought to be inclusive. It is an un-auditioned SATB choir that welcomes all voices and sexual and gender identities, including heterosexual allies, from all walks of life (RCWW, n.d.).

Throughout its 27-year history, the choir has had a profound influence on members lives, and in the local community. As social and political considerations of LGBTQ+ people change, so too has the choir’s role changed in the community and for its membership. Originally a refuge and a communal hub for queer people, and a showcase of queer artistry, the choir now also provides a space for queer people young and old to resist assimilation and homonormativity3, and find networks of intergenerational queer wisdom. It has also had a significant impact on local history: members of the rainbow chorus were part of the lawsuit that allowed same sex civil partnerships, and a triple wedding of chorus members were the first same sex couples to be married in this region. Some of its members were the first same sex couples openly adopt children (CBC News, 2012).

Self-Positioning

As a young queer person growing up in Guelph, I have long admired the work of the Rainbow Chorus. Several friends and family members have sung in the choir over the years, some of whom have met their partners and spouses through choir. I feel incredibly fortunate to have grown up around a thriving supportive, intergenerational queer community. This research, and my engagement with community music, stems from the knowledge of how important the Rainbow Chorus has been in the lives of so many people, and the strong community it fosters.

Research Questions and Methodology

My research questions are:

1. What role does the Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington (RCWW) play

a. in members lives,

b. and in the wider community?

2. What is different about this community, as opposed to other community choirs that don’t specifically center marginalized identities?

3. How does the Rainbow Chorus community build, maintain, and support itself and its members?

I approached these questions using a mixed method, grounded theory approach (Cresswell & Poth, 2018; Mayoh & Onwuegbuzie, 2015). I conducted an online survey of the RCWW membership, as well as several other local community choirs as a control group.

From the surveys, RCWW members self-selected to be interviewed for a more in-depth discussion than the survey questions. The survey included quantitative data and qualitative open-ended questions (see Appendix 1). In total, there were 41 survey responses from RCWW, 32 from the control community choirs, and 23 participants were interviewed over the course of late June to mid-August of 2020. There was a wide range amongst the respondents regarding their tenures in the choir, their genders, and sexualities. After performing a statistical analysis of the quantitative data from the surveys, NVivo coding was used to analyze the qualitative survey data and interview transcripts.

Findings

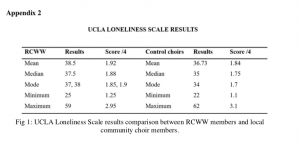

One of the things I wanted to investigate was the phenomenon of queer loneliness. As discussed earlier, queerness can often be a profoundly isolating axis of marginalization, with increased loneliness among queer people being a well-documented phenomenon (Hobbes, 2017). I was curious as to whether the community and relationships in RCWW would have a countering effect. I used the UCLA loneliness scale to gauge the loneliness of RCWW members and compared it to UCLA loneliness scale results from the other, predominantly cisgender and heterosexual, community choirs. The UCLA loneliness scale is a 20-item scale designed to measure one’s subjective feelings of loneliness as well as feelings of social isolation (Russell et al., 2011). Participants rate each item on a scale from 1 (Never) to 4 (Often). Results are scored between 1-4, with higher results indicating more loneliness and social isolation (see Appendix 2).

The results were promising: on average, members of RCWW scored low in loneliness, and were hardly any different than the loneliness score of the ‘non queer’ choirs. While it cannot be definitively said that these choristers are less lonely than the general population, queer or otherwise, in this region, it is worth noting that 68% of RCWW members indicated that their answers to the loneliness scale questions had changed since joining the choir, as opposed to just 48% of the control community choir members. Both RCWW members and the community choirs indicated that being in choir has had a significant positive effect on their personal and social wellbeing, including continuing social connection during the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were notable differences in survey responses from the control community choirs and RCWW members. In response to the questions ‘what drew you to the choir?’ and ‘what do you like about the choir?’ the community choirs most common answers, by far, were simply wanting to sing, and being able to make music together with a group. Of course, many RCWW members joined the choir to sing and make music, and many expressed a great deal of pride in the caliber and artistic merit of the choir. However, far more participants emphasized that the thing that drew them was a desire to connect with the LGBTQ community and meet other queer people in the area, in a space that is not a bar or a club. In addition to singing, they liked the community that the choir fostered, its judgment free space, and the friendships that they had made there. Many respondents expressed sentiments such as:

I was searching for community. I had been through a breakup and had only recently come out, and when I found Rainbow Chorus, I knew it was for me.

Others talked about the value of the choir in creating an intergenerational space where youth and elders can learn from each other.

I think what makes the choir really unique is the diversity of age ranges. I think it’s really rare in the queer community, and in communities in general, to be in a conscious space that has such a diversity of age ranges. You know? Because then you get this diversity of history, and you’ve got this diversity of new ideas.

[…] it’s been a big, big relief to have those older voices, talking to [other members] about “what’s it like to be a lesbian mom?” You know what I mean? Things that you can’t learn from reading about. It’s so valuable, to experience their stories and to hear their stories and learn from it.

There is a wealth of communal information and intergenerational wisdom, which is not available anywhere else. Singing together is of course a crucial part of this community, but there is clearly so much more to it than ‘just’ making music. Collective music making for the Rainbow Chorus is not only artistically meaningful, but a socially transformative experience.

The interview process (conducted via Zoom video conferencing) was often an emotional experience. Many people highlighted how ‘everything always managed to get sung about, somehow.’ Some people talked about the early days the choir, which started out as a small group of people wanting to create a space of joy to celebrate and comfort one another, and to raise the profile of LGBTQ+ people in the area. We talked about the challenge of fund raising early in the choir’s existence — when businesses would slam the door on them for soliciting sponsorship for a gay choir — and the creative ways people managed to fundraise regardless. They shared joys: weddings and raising children and finding chosen family, and sold-out concerts and festivals. They emphasized how participating in choir was a life-giving form of activism.

Other LGBTQ events or groups that I’ve been part of have had a fairly strong political focal point. And I think we do too, but, it’s more joyful, and it’s more celebratory. There’s a lot of work to activism for sure, and it is emotional work, and it can really get you down. Whereas the kind of activism we do is really joyful.

Music touches people on a different level. And despite my ability to make arguments I think art in various forms often changes minds more than arguments do…. it reaches people at a different level, including within ourselves when we’re doing it, but also the people we’re singing to.

They also shared sorrows, mental health struggles, fractured relationships, internal conflicts, and loss. The music and the community are inextricably part of how members have process major life events; the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Well, the choir has literally saved my life […] I struggle with depression and, and having the consistency of choir, and going to a place where I am cared for and supported has literally saved my life.

Many people talked about the pain of recent struggles within the community, and the ways the choir has tried to heal from that. We discussed how the choir has struggled in the past, and though far from perfect, they were fiercely proud of the work they had done to overcome strife and find meaningful, collaborative ways to move through conflict.

[…] we learned the hard way that we have more to learn. There’s been some really good healing that has happened since then, we’re in a good place, and trying to keep on a good path about that… anti-oppression training was part of that, it was making a commitment to that.

These interviews were even more emotionally charged because of the grief and loss of community caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the research took on a renewed significance because of it. Members were keen to stay connected to the choir and celebrate their community through participating in this research, celebrating the choir and their accomplishments even when they had to be apart.

Discussion

Working through the grounded theory methodology, I sought to find a theory that would do right by all these stories, that connected them all without neglecting any one person’s experiences or journey. A theory that would showcase the incredible complexity of the social, musical, and relational transformations occurring in this community. Eventually I settled on the theory of queer utopian musicking, a synthesis of concepts from queer theory and musicology.

Queer utopianism is a term that describes a movement towards a society where the full diversity of human expression and relationship can be explored and celebrated, without judgement, fear, reprisal, or castigation. In the words of noted queer utopian thinker Jose Esteban Muñoz:

Queerness is not yet here. Queerness is an ideality. Put another way, we are not yet queer, but we can feel it as the warm illumination of a horizon imbued with potentiality. We have never been queer, yet queerness exists for us as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future. The future is queerness’s domain.’ (Muñoz, 2009)

Queer utopianism is a goal, a striving, an embodied practice of living relationship that already exists in microcosms of social space, mediated within that space’s culture (Muñoz, 2006). It is a space that seeks to de-center and de-normalize heteronormative narratives and cultural scripts. A space where our presumed reproductive capabilities, self-expression, and desires are not central defining aspects of our personhood, determining our legal rights and social status. This process of reimagining benefits not only queer people, but all people, by critically examining social and cultural scripts, and urging us to imagine different ways of existing, that do not limit our relational potential. It rejects homonormativity, the assimilationist concept whereby queer identities are rendered palatable to mainstream cisgender-heterosexual sensitivities (Ellis, 2019).

Dr. Jules Balén (2017) describes this as a counter-storying practice: telling our stories, combating dominant cis-hetero-normative social narratives in order to push back against the silencing and censorship of queer voices. This helps provide a space that gives us back agency and full personhood, a space to explore the manifold possibilities of human connection.

Musicking is a term coined by Christopher Small in his 1998 book by the same name. In it, he describes music as a process, a verb, rather than a static object. He writes ‘musicking shows us ideal relationships, affirming ourselves and anyone listening’ (p.183). Through the act of collective music-making as a group as well as listening to it, ‘those taking part are, in effect, saying to themselves and anyone watching and listening, “this is who we are”’ (p.212). Who we are is how we relate to each other. Indeed, ‘to musick is not just to discuss the relationships in our world, but to actually experience those relationships’ (Small, 1998, p.98).

Through the process of this queer utopian musicking, the choir creates a space whereby a new existence can be imagined. Members of the choir, as well as their audiences, are able to explore new relationships, ways of being, and ways of perceiving themselves and each other. For the audience, they are able to witness queer joy, queer celebration and queer people living authentically and unapologetically. For the members, they get to connect to a diversity of people that they might not otherwise meet, engage in negotiated learning, and participate in a creative, artistically meaningful exploration of self and community. These relationships, these forms of self-expression, are lived out through repertoire choices, by small gestures of affirmation, encouragement, and moments between members, in performance and rehearsal and simple day to day. The group resists the pull of assimilation into the dominant heteronormative culture, instead celebrating the diversity of its members and uplifting marginalized voices. The RCWW engages in queer utopian musicking, where the full spectrum of human expression, desire, experience, and relationships, are explored through the interface of choral singing.

Conclusion

The RCWW has been a powerful site of personal and communal transformation in the Waterloo Wellington region for the past 27 years. The chorus plays a huge variety of roles in members lives, from support system and social contact to creative outlet and a place to experiment with authenticity. In the wider community, they are ambassadors, a thriving representation of queerness in the Waterloo-Wellington region. They are empowered through their connections in choir to advocate for themselves and their community. This choir is different from other choirs for many reasons, but in large part because it is an intentional space for LGBTQ+ people. It was created by and for LGBTQ+ people, and it takes its mission of being a safe space very seriously. They engage intentionally with one another, celebrating joy and meaningfully supporting each other through difficult times. When conflict and strife arise, they seek to move through it in a sensitive, mediated way, ensuring that all members have the space and safety to express themselves. Through this process of queer utopian musicking, they negotiate relationship and community in this beautiful queer way. Thus, the RCWW community is able to support its members and simultaneously expand our understanding of the human capacity for connection and artistic exploration. This is a model for community music groups the world over: using music to realize authentic connection between members and enact change in their communities.

Endnotes:

- Heteronormativity: the way heterosexuality positions itself as neutral, normative, and dominant (Manning, 2015).

- It is important to note that there were many queer affiliation groups, support networks, clubs, and activist collectives across the country, but often there is little documented or accessible historical record of them, particularly outside of major urban centres such and Toronto and Montreal

- Homonormativity: a set of politics that does not contest the dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them (Duggan, 2003, in Manning, 2015). These are practices that affirm the normalcy of some gay and lesbian people within a capitalist and colonialist framework at the expense of further marginalizing other queer people, including trans, non-binary, and two-spirit peoples (Manning, 2015).

References

Altman, L. K. (1982, May 11). NEW HOMOSEXUAL DISORDER WORRIES HEALTH OFFICIALS (Published 1982). The New York Times.

ANNA Crusis Womens Choir. (n.d.). ANNA Crusis Womens Choir. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://annacrusis.org/

Balén, J. (2017). A Queerly Joyful Noise: Choral musicking for social justice. Rutgers University Press.

Bird, F. (2017, July 1). Singing Out: The function and benefits of an LGBTQI community choir in New Zealand in the 2010s [Text]. https://doi.org/info:doi/10.1386/ijcm.10.2.193_1

Byerly, I. B. (2013). What Every Revolutionary Should Know: A musical model of global protest. In The Routledge History of Social Protest in Popular Music (pp. 229–247). Routledge.

Cacioppo, J., & Patrick, W. (2008). Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. W. W. Norton & Company.

Canadian Queer History Timeline. (2018, September 17). Canadian Centre for Gender and Sexual Diversity. https://ccgsd-ccdgs.org/queer-history/

CBC News. (2012, January). TIMELINE | Same-sex rights in Canada | CBC News. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/timeline-same-sex-rights-in-canada-1.1147516

Cresswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Chapter 4: Five Qualitative Approaches to Inquiry: Grounded Theory. In Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design (4th ed., pp. 82–90). SAGE publications.

Ellis, R. (2019, May 24). Liberation vs Assimilation in Queer Cinema. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2KvWP5_Q9k

GALA History. (2011, October 5). Gala Choruses. https://galachoruses.org/about/history

Glatter, J. (2016, June 27). A Brief History Of Gay Pride. The Odyssey Online. https://www.theodysseyonline.com/history-gay-pride

Glick, M. L. (2011). Singing, health and well-being: A health psychologist’s review – ProQuest. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind & Brain, 21(1 and 2), 32. https://doi.org/10.1037

History | Gala Choruses. (n.d.). Retrieved September 14, 2020, from https://galachoruses.org/about/history

History of Canadian Pride | QueerEvents.ca. (n.d.). Queer Events. Retrieved January 18, 2020, from https://www.queerevents.ca/canada/pride/history

Hobbes, M. (2017, March 2). Why Didn’t Gay Rights Cure Gay Loneliness? The Huffington Post. https://highline.huffingtonpost.com/articles/en/gay-loneliness/

Home | LEGATO European Association of LGBTQ+ Choirs. (n.d.). LEGATO Choirs. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.legato-choirs.com

Judd, M., & Pooley, J. A. (2014). The psychological benefits of participating in group singing for members of the general public. Psychology of Music, 42(2), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735612471237

Manning, E. (2015). AIDS, Men, and Sex: Challenges of a Genderqueer Methodology. In S. Strega & L. Brown (Eds.), Research as Resistance (2nd ed., pp. 199–220). Canadian Scholar’s Press.

Mayoh, J., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2015). Toward a Conceptualization of Mixed Methods Phenomenological Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(1), 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689813505358

Muñoz, J. E. (2006). Stages: Queers, Punks, and the Utopian Performative. In The SAGE Handbook of Performance Studies (pp. 9–20). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976145

Muñoz, J. E. (2009). Cruising Utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. New York University Press.

Our Story | SFGMC. (n.d.). San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.sfgmc.org/about-sfgmc

RCWW. (n.d.). RCWW | Rainbow Chorus of Waterloo-Wellington. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from http://rainbowchorus.ca/

Rosenthal, R., & Flacks, R. (2016). Part 1: An Introduction to the Music-Movement Link. In Playing for Change: Music and musicians in the service of social movements. Routledge.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (2011). Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale [Data set]. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01011-000

Scherschligt, D. (2017, December 5). I’m Gay and Christian–and Oh Yea, I’m HIV Positive, Too | by Donald Scherschligt | Reaching Out | Medium. Medium.

https://medium.com/reaching-out/im-gay-and-christian-and-oh-yea-i-m-hiv-positive-too-6d1627a58c6f

Thirty Years of HIV/AIDS: Snapshots of an Epidemic. (n.d.). The Foundation for AIDS Research. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://www.amfar.org/thirty-years-of-hiv/aids-snapshots-of-an-epidemic/

Willingham, L. (2005). What Happens When People Sing? A Community of Voices: An investigation of the effects of belonging to a choir. The Phenomenon of Singing International Symposium V, 5, 328–346.

Appendix 1:

Survey questions:

- What is your age?

18-29 / 30-39/ 40-49/ 50-59/ 60-69/ 70+

- What is your gender? _______________________

- What is your sexuality? _______________________

- Total years of membership in the choir (continuous or not) ____

- Please indicate how often each of the statements below is descriptive of you. Note that your response may be affected by the current COVID19 situation. Answer as honestly as you can as it concerns your life in general, the present moment. (UCLA Loneliness Scale)

| Never (1) | Rarely (2) | Sometimes (3) | Often (4) | |

| 1. I feel in tune with the people around me (1) | O | O | O | O |

| 2. I lack companionship (2) | O | O | O | O |

| 3. There is no one I can turn to (3) | O | O | O | O |

| 4. I do not feel alone (4) | O | O | O | O |

| 5. I feel part of a group of friends (5) | O | O | O | O |

| 6. I have a lot in common with the people around me (6) | O | O | O | O |

| 7. I am no longer close to anyone (7) | O | O | O | O |

| 8. My interests and ideas are not shared by those around me (8) | O | O | O | O |

| 9. I am an outgoing person (9) | O | O | O | O |

| 10. There are people I feel close to (10) | O | O | O | O |

| 11. I feel left out (11) | O | O | O | O |

| 12. My social relationships are superficial (12) | O | O | O | O |

| 13. No one really knows me well (13) | O | O | O | O |

| 14. I feel isolated from others (14) | O | O | O | O |

| 15. I can find companionship when I want it (15) | O | O | O | O |

| 16. There are people who really understand me (16) | O | O | O | O |

| 17. I am unhappy being so withdrawn (17) | O | O | O | O |

| 18. People are around me but not with me (18) | O | O | O | O |

| 19. There are people I can talk to (19) | O | O | O | O |

| 20. There are people I can turn to (20) | O | O | O | O |

- (RCWW ONLY) Do you have close friends who are LGBTQ+?

Yes/ No

- (COMMUNITY CHOIRS ONLY) Would you say you have many close friends?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- (RCWW ONLY) Would you describe yourself as being involved in the LGBTQ+ community?

Yes/ No

- (RCWW ONLY) Are you part of any other LGBTQ+ groups in your community aside from choir?

Yes/ No

- (RCWW ONLY) If you answered yes to question 3, which groups are you involved with?

- Do you feel like your identity has shifted while you’ve been a member of the choir?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Do you feel that your social circle or social life has changed as a result of being a member of the choir?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- (RCWW ONLY) Has choir broadened your contact with other LGBTQ+ people?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Have you formed any close relationships through being in choir?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Would you say that your answers to the above loneliness scale have changed since joining the choir?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Has choir had a positive impact on your personal wellbeing or mental health?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Has choir had a positive impact on your social or community life?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Has choir membership been a source of social contact since the initiation of physical distancing measures?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- Has your relationship to or perception of your choir changed since the initiation of physical distancing measures?

Yes/Somewhat/No

- What initially drew you to the choir?

- What is something you like about the choir?

- What is something you think could be improved about the choir? (Related to COVID19 or in general day-to-day)

- What space does choir provide that is different or unique? (Related to COVID19 or in general day-to-day)

- How has physical distancing restrictions impacted your connection with your community?

- (RCWW ONLY) If you are interested in being contacted for an interview, please provide your name and email address or phone number for follow up contact. Your contact information will not be recorded with your survey responses.