Lawler, E. (2021) Transform-Download PDF

York St John University

Abstract

Initially developed by Arnold van Gennep in 1909, the anthropological concept of “liminality” (the intervening period of ambiguity when transitioning between two social states during a rite of passage) has since been fruitfully applied to a broad spectrum of scholarship. Perhaps most notable was Victor Turner’s extensive development of the idea in the mid-1970s, where he invented the term “liminoid” to depict liminal-like occurrences of transitional ambiguity within the context of more modern society. Community music activity, as events that are out of the ordinary flow of the everyday and in many instances critical of the economic/political/societal status quo, could be said to typify liminoid phenomena. Because liminoid events subvert the normative social structures of society, liminoid spaces hold much transformative potential. This offers an explanation as to how and why community music might facilitate social transformation. It is concluded that, although community music is indeed a subversion of the status quo, both structure and antistructure are essential within the fabric of society, implying that community music is still to some extent confined within the constraints of – and therefore dependent upon – the very norm that it critiques.

Key words: liminal; liminoid; community; society; sociology; anthropology

Introduction

First coined by anthropologist Arnold van Gennep (1909) in his book Les Rites de Passage, the term liminality has since been built upon and used as a concept over the course of many decades within a wide gamut of academia including religion (St. John, 2008), tourism (Graburn, 1978), ageing (Mackay Yarnal, 2006), international relations (Rumelili, 2003), death-related care (Helsel, 2009), and Brexit (Reed-Danahey, 2020). After unpacking the terms “liminal” and “liminoid” and critiquing their use a framework, I shall use these concepts as a lens to demonstrate how community music activity could be framed as a liminoid event before illustrating how, as such a subversion of the status quo, community music holds socially transformative potential.

For the purpose of this article, community music can be broadly understood as ‘an active intervention between a music leader or facilitator and participants’ (Higgins, 2012, p. 21). From my positionality as an academic student and developing practitioner within the field in the UK, this is perhaps the most succinct and representative summary of my perception of community music. This is not at all to suggest that this interpretation is singular or universal – what constitutes community music is a widely discussed topic within the field, with several authors (Phelan, 2008; Veblen, 2008; Schippers and Bartleet, 2013; Veblen et al., 2013) ruminating upon the matter and usually finding fault with generalizing definitional approaches that ‘diminish the particularity of event-based activities, and strips them of the specificity of cultural, political or social context’ (Phelan, 2008, p. 145). However, clarifying and consolidating this conceptualisation, whilst also noting that it is potentially better viewed through a postmodern, praxial lens rather than a statically defined one, is necessary to remain within the scope of this article.

Just as my aim is not to debate how best to articulate community music, it is also not to scrutinize the term transformation, its definition, forms, or ethics. Rather, this article is a philosophical exploration that suggests a framework offering a sociological explanation for the well-documented empirical evidence that community music activity has the potential to facilitate some sort of change on some sort of level; the concept of transformation is a prevalent theme in much contemporary community music literature, appearing frequently within the IJCM (Smilde, 2010; Adkins et al., 2012; Boeskov, 2017; Sheridan and Byrne, 2018; Howell et al., 2019) and is the subject of a whole section of the Oxford Handbook of Community Music (2018).

Finally, it is worthy to note here that a potential limitation in my research is that there is very little existing literature that has drawn together liminality and community music, meaning that there is not much published data directly supporting my linking of the two fields – this is perhaps particularly problematic since community music is a relatively new field and the concept of liminality is considerably older. However, as community music could be considered within the frame of both the fields of sociology and social anthropology1, and, as previously alluded to, the idea of liminality demonstrably appears in a diverse range of disciplines right up until the present day, there is clear justification in this pairing.

Liminality

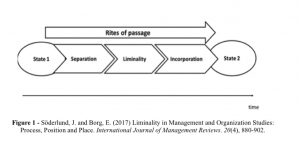

The word liminality originates from the Latin limen meaning threshold; ‘literally, a threshold divides two spaces’ (Turner, 1985, p. 205). Van Gennep referred to this to describe the intervening transitional period between two states during rites of passage. In his words, rites of passage could be defined as ‘rites which accompany every change of place, state, social position and age’ (van Gennep, 1909, cited by Turner, 1969/2017, p. 94); events such as (as his original lengthy subtitle2 identified) ‘hospitality, adoption, pregnancy, delivery, birth, childhood, puberty, initiation, ordination, coronation, engagements and marriages, funerals, the seasons etc.’ (van Gennep, 1909/2019, cited by Kertzer, 2019, pp. xvi-xvii). His tripartite model (see Figure 1 below) describes all rites of passage to have three stages: Separation, Liminality, and Incorporation.

During the Separation phase, subjects are ‘disjointed from the everyday flow of activities’ (Turner, 1969/2017, p. 94). This is followed by the ‘ambiguous’ (Turner, 1969/2017, p. 94) and uncertain transition phase of Liminality, before the third and final Incorporation phase (also known as Reaggregation or Reincorporation), completing the rite of passage so that the subject is once again in and of a relatively stable social state. Throughout, such transitions are managed for and by the subjects in the form of rituals and symbols – for instance, during the rite of passage of marriage, ceremonies such as the exchanging of rings, the wearing of distinctive garments, dancing, the consummation of the marriage etc. all signify and manage the transition between the social status of being single to that as part of a couple.

As community music may be ‘considered within the frame of postmodernism’ (Higgins, 2008, p. 35), where the clear-cut, static boundaries of universal truth are constantly being examined, critiqued, and challenged, the general concept of liminality resonates with the notions of community music as a postmodern field. However, a more accurate description reflecting its contemporariness would be liminoid.

Liminoidity

It was cultural anthropologist Victor Turner who took van Gennep’s initial theorizing and developed it so that it could be applied to more than what van Gennep (1909/2019) problematically referred to as “semi-civilized societies”3; ‘traditional […], non-Western societies’ (Routledge Companion Websites, 2012a). Turner invented the term liminoid, which he used to depict liminal-like events occurring within the context of more modern, industrialized society; ‘“liminoid” resembles without being identical with “liminal”’ (Turner, 1974, p. 64). This could encompass a vast range of phenomena such as a football game or a rock concert. During these events, subjects are neither continuing as ordinary citizens (pre-liminal), nor have they re-emerged and integrated back into everyday life (post-liminal); they are in a state of liminality, but the situation of the event within modernity makes it liminoidity (Versteeg, 2011). Able to apply these ideas to both his fieldwork amongst the Ndembu people of north-western Zambia4 and observations made from his positionality as a British anthropologist during the mid- to late-20th century, Turner distinguished the liminal from the liminoid in five ways:

1) Firstly, liminal phenomena ‘tend to predominate in tribal and early agrarian societies’ (Turner, 1974, p. 84), whilst liminoid phenomena ‘flourish in societies […] bonded reciprocally by “contractual” relations’ (p. 84). This difference can also be articulated through Durkheim’s (1893/2010) concepts of organic and mechanical solidarity: mechanical solidarity refers to the social cohesiveness of small, undifferentiated groups sharing common beliefs and values (Britannica, n.d. a), whilst organic solidarity is the social cohesiveness of groups differentiated by a complex division of labour, i.e., arriving out of individuals’ interdependence upon each other’s services. Alternatively, a similar idea is also expressed through Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft dichotomy5 ‘constructed to capture the social transformation from pre-modern to modern society’ (Sandstedt and Westin, 2015, p.135). These different articulations all serve to illustrate that, according to Turner, liminoid events occur within “modern” societies rather than “tribal” communities.

2) The second key difference between the liminal and the liminoid are the rhythm of the events. Liminal phenomena characteristically occur cyclically and/or in connection with life-cycle processes and events such as the seasons or developmental milestones, whilst liminoid events happen more ‘erratically and idiosyncratically’ (Spiegel, 2011, p. 13).

3) Liminal phenomena are ‘of collective concern’ (Spiegel, 2011, p. 13) to all members of the unit due to the shared beliefs and values of mechanical solidarity acting as a ‘collective conscience’ (Britannica, n.d. a). Liminoid events, meanwhile, are more individualistic due to the more individualized nature of societies based on organic solidarity, ‘though they often have collective or “mass” effects’ (Turner, 1974, p. 85).

4) Unlike liminal events, which are central to and maintained by the central processes and social structure they exist alongside and within, liminoid phenomena ‘develop apart from the central economic and political processes’ (Turner, 1974, p. 85). This tends to make the activities that happen within them ‘experimental and potentially socially transformative’ (Spiegel, 2011, p. 13).

5) Finally, and closely linked to this, liminal spaces serve to maintain the existing social structure and are therefore ‘eufunctional’ (Turner, 1974, p. 86) to the maintenance of the norm. In contrast, liminoidity subverts the status quo, with the activities happening within the space representing or acting as critiques of the mainstream structures and organisations. Turner even refers to liminoid phenomena such as books, plays, paintings, films, etc. as ‘revolutionary manifestoes’, ‘exposing the injustices, inefficiencies, and immoralities of the mainstream economic and political structures and organizations’ (Turner, 1974, p. 86); the liminoid has potential as a catalyst for the transformation of social structures. The encapsulated environment of the football match or the rock concert allows subjects the opportunity to subvert social norms; to present themselves largely without the same constraints of the external economic, political, and social hierarchies that normatively dictate their interactions. Here, we can already see how this is of relevance to community music practice, which is rooted in sociopolitical activism (Higgins, 2012).

Problematising this framework

Although Turner’s contribution to this body of knowledge is invaluable because, unlike van Gennep, he takes structural functionalism6 into account, there are definitely still some issues arising from his distinctions.

Perhaps the most important of these concerns is that Turner has reduced an incredibly complex and fluid concept to a mere binary. It could easily be misconstrued that Turner implies the liminal and the liminoid are mutually exclusive phenomena, which simply cannot be the case; there will undoubtedly exist certain limen-type events/spaces that fulfil a mixture of his criteria, regardless of whether they are constructed within a pre-modern, modern, or even post-modern social context (Spiegel, 2011, referencing Douglas, M., 1978). ‘[Turner’s] apparent modernist commitment to a binary […] assumes a neat break between the pre-modern and the modern’ (Spiegel, 2011, p. 14), which, from a postmodernist perspective that does not seek such a “universal truth”, does not facilitate the academic and scholarly creativity necessary within contemporary arts research (Routledge Companion Websites, 2012b).

Turner’s dichotomising of liminal and liminoid is, in fact, somewhat strange considering his acknowledgement of the great complexity of social structure and his critique of such binary models in the very same paper. Even he describes his delimitation as ‘crude’ and ‘preliminary’ (p. 84), whilst also having contradictorily said that ‘[i]t is not surprising that liminality itself cannot escape the grip of these strong structuring [binary] principles’ (p. 84). Reconciling this tension, Spiegel (2011) proposes that Turner needed instead ‘to construct the distinction by conceptualising the liminal and the liminoid as opposing poles on a continuum between two ideal types’7 (p. 15). This would preserve all his very valid observations of differences between the liminal and the liminoid, whilst also accounting for the nuances and complexities of reality.

Community Music as Liminoid

Emerging from this examination of liminality and liminoidity, I suggest that community music activity could be described as a liminoid phenomenon. If we assume now that Turner’s five characterisations of liminal and liminoid are actually “ideal types” (see endnote 7), as Spiegel suggested, we can see how community music activity might typify liminoid phenomena.

1) Firstly, community music as I have experienced it in the UK tends to take place within the context of “modern” society; within settings more typical of Gesellschaft, where the social fabric is held together by the modernist values of organic solidarity and contractual relationships. As previously acknowledged, this will not be the case for all forms of community music activity, though much of the discourse remains objectively dominated by the voice of the Western world/Global North.

2) Secondly, the rhythm of community music activity is not dependent on nature or other cyclical events (as is the case for liminal phenomena) but instead is defined by the idiosyncrasies of the group(s) of individuals it concerns. This is due to the more individualistic values found within societies built upon organic solidarity; in social structures where interactions are mainly contractual and based upon reciprocal need for each other’s different skills and services. Community music activity takes place scheduled in the interests of practitioners and their participants, not necessarily the seasons or life processes.

3) Linked closely to this, community music activity therefore also demonstrates the third criterion for liminoidity in that it involves ‘characteristically individual products’ (Turner, 1974, p. 85) by utilising ‘deliberately tailored’ musical approaches (Deane et al., 2011, cited by Deane, 2018, p. 323). “Product” is, of course, a problematic term within community music, entangled as it is within an often-dichotomised conceptualisation of “process/product”. However, here it is referring to the signs and symbols associated with the event. One community music practice or group will have a different set of idiosyncratic signifiers to another, even if they occur within the same society. Hence, the “products” are individualistic, rather than having universal meaning as is more the case for ritualistic symbols within liminal events. In this way, the “products” can be idiosyncratic to specific community music groups whilst also having the collective effect that Turner (1974) spoke of: practitioners concern themselves with balancing not only the needs of each individual participant but also those of the whole group and their wider community.

4) Looking at the history of community music (particularly within the UK), we can clearly compare community music to liminoid phenomena, which develop ‘along the margins, in the interfaces and interstices of central and servicing institutions’ (Turner, 1974, p. 85). Community musicians are ‘boundary-walkers’ (Kushner et al., 2001, cited by Higgins, 2006, p. 5) that ‘inhabit margins, borders, limitations, and edges’ (Higgins, 2006, p. 5). Though Higgins’s use of the term was used in a different and far more positive, empowering way than Kushner et al., they both illustrate here the limen-like nature of community music practice. As a result, community music activity exists in a multifaceted, plural, and fragmentary manner as it has largely developed aside from and without the assistance of the central economic and political systems.

5) In fact, moreover, community music is ‘derived […] from a 1960s radicalism’ (Deane, 2018, p. 323), rooted in political activism – indeed, a whole section of the Oxford Handbook of Community Music (2018) is dedicated to Politics. This fulfils the final characteristic of liminoid phenomena in that community music activity is often a subversion of the status quo. Its widespread and continuing concern with social justice (Hayes, 2008; Lee, 2010; Shiloh and Lagasse, 2014; Sunderland et al., 2016) and cultural democracy (Graves, 2010; Brøske, 2017; Currie et al., 2020; Gibson, 2020) demonstrates a sustained commitment to the subversion of the enforced hierarchical structures of the society/societies in which it takes place. In terms of functional sociology, this means it could be described as dysfunctional or antistructure: it concerns social structure that deliberately counteracts the mainstream, implying a disturbance of the existing social structures and patterns in a critique of the norm. This once again illustrates how community music activity might be perceived as liminoid.

Liminoidity as Transformative Potential

‘Social transformation are processes in which individuals’ or groups’ relations to themselves, each other and their surrounding world are transformed’ (Boeskov, 2017, p. 86). Transformation is a concept that has become commonly drawn upon in community music literature (Humphrey, 2020, p. 40), a critical facet of community music work. However, actual theory as to how arts participation might be a mechanism for social change ‘is not yet well explicated’ (Dunphy, 2018, p. 201) – because of the highly fluid, context-dependent nature of so many of the concepts within the arts and social sciences, it is (at best) incredibly difficult to pin down even definitions of terminology, let alone hypothesize a universal explanation for their occurrences. Using liminoidity as a conceptual lens offers a sociological/anthropological perspective that might allow us to understand community music as transformative practice. Community music is ‘a thoughtful disruption [and] denotes an encounter with “newness”, a perspective that seeks to create situations in which new events innovate and interrupt the present toward moments of futural transformation’ (Higgins, 2015, p. 446); community music can be considered as a liminoid practice. Liminoidity’s characteristic subversion of the status quo fosters an isolated space that is free from the constraints of existing social structures. As a result of this, there is much transformative potential within these spaces, because the subjects’ social status outside the liminoid space is temporarily not relevant within the protected enclosed environment – at least, not in the same way as it is outside it. This is, perhaps, in parallel with the idea of creating a safe space (Higgins, 2012; Howell et al., 2019; Henley and Parks, 2020) in community music, as participants are protected from the normative judgement they might receive in and/or from the outside world. Within these liminoid spaces, participants may experience the equalising, undifferentiating bond of communitas (Turner, 1969) as they collectively encounter liminality.8 Personal relationships, rather than social obligations and preconceptions, may be stressed, allowing participants to reimagine how they are perceived. A practical example of this could be a community choir for care-givers. Being a participant in a choir recontextualises a subject’s identity, which offers the opportunity for its redefinition. This is not to say that their identity as a care-giver is diminished or overlooked – rather it is acknowledged without preconception. In this way, community music activity’s liminoidity can subvert social norms.

Boeskov (2017) suggests that this anthropological perspective ‘substantiates already established ideas of the transformative potential of active music making’ (p. 86), particularly Small’s (1998) concept of musicking9, which he feels ‘exemplif[ies] general assumptions towards [the idea of transformation] held in the field of community music’ (Boeskov, 2017, p. 86). In fact, he furthers this by expressing his opinion that ‘emphasizing Turner’s notion of liminality rather than Small’s concept of ideal relationships leaves us with a less idealistic but more genuine idea of what community music practices might mean to marginalized groups’ (p. 95). An implication of this is that viewing community music through such an anthropological lens might assist community music researchers and practitioners in taking a more objective stance when reflecting upon their practice.

As a final point, I find it interesting to note that, though liminoid phenomena such as community music subvert normative social structures, the events themselves are still to some extent confined within their constraints. For example, community music projects and practitioners are, to some degree, reliant on external funding. This is evidenced in Humphrey’s (2020) critical discourse analyses of the word transformation (amongst others) within the Sounding Board journals10: ‘it is clear that the discourse surrounding community music became more focused on the health and well-being agenda that was at the crux of the Labour government’s policies’ (p. 56). Kelly (1984) went as far as to say that community artists ‘have become foot soldiers in [their] own movement, answerable to officers in funding agencies and local government recreation departments’ (p. 15). Though circumstances have clearly changed dramatically since the 1980s, the issue of funding (particularly the lack thereof) within community music is also mentioned extensively by Higgins (2012); times have changed, but not so dramatically that community music projects are no longer reliant upon financial capital. Therefore, community music (and by extension potentially also other – perhaps even all – liminoid phenomena…), though subversive and critical of the status quo, are still unavoidably, inextricably bonded within and to the normative.

Conclusion and Implications

In conclusion, van Gennep’s concept of liminality has provided a useful starting point for both this article and an extensive catalogue of research spanning a broad range of disciplines. However, as premonished during my introduction, it is limited by its age, with dated language in particular being very problematic – especially when being applied to a field such as community music which tends to be very conscious and critical of the words used within its discourse. Turner’s development of “liminoidity”, though still presenting issues, considerably modernizes van Gennep’s theory and has done much to facilitate its application within contemporary research. As a relatively new academic field, community music is far more accurately described as “liminoid” than “liminal”, and, as has been demonstrated, has potential to fulfil all five of Turner’s characteristics of liminoid phenomena.

This being said, Turner’s binary distinction between liminality and liminoidity is perhaps not altogether the most creative or representative model reflecting the nuances of today’s reality. Nonetheless, describing community music activity as liminoid phenomena does offer an explanation as to how and why community music participation has potential as a mechanism for social change through its subversion of society’s normative social structure. When Turner’s characterizations are interpreted as “ideal types”, as suggested by Spiegel, we as practitioners might be able to take a less idealised and more objective stance when reflecting upon and critiquing our practices – vital in an often polarized world. This not only has implications within the field of community music, but also any domain that concerns itself with liminal-type events or social transformation – other creative arts, information and communications technology, and education to name but a few.

As a final thought, it might be important to the future of the field of community music to consider that both structure and antistructure are essential within the fabric of society. Neither idea can be fundamentally conceptualised without the other; without structure there cannot be antistructure. Therefore, as much as community music activity might act as a critique of society’s flaws and inequalities as a phenomenon towards the liminoid end of a liminality/liminoidity continuum, it is also objectively dependent upon them for its own very conceptual existence.

Endnotes:

- In oversimplified terms, sociology (a sub-domain within anthropology) focusses on society and social structures whilst anthropology more broadly concerns the study of human cultures and behaviour and the evolution thereof.

- As Kertzer (2019, pp.xvi-xvii) points out, van Gennep’s initial subtitle was omitted in the translation of the book in 1960 by M. Vizedom and G. Caffee. All other editions of Les Rites de Passage seem to be republications of this same translation, with various added author’s notes and forewords.

- This term is obviously dated and problematic in several ways; as acknowledged by Richard Schechner (Routledge Companion Websites, 2012a), its loaded colonial Western-centrism is neither applicable nor tolerable within today’s context. However, the basic theory still remains fruitful and provides a starting point for exploration and discussion.

- The Ndembu people of Mwinilunga District in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) were the subjects of Turner’s ethnographic research on African ritual. He lived among and studied the tribe during 1950-1952 and 1953-1954 (Turner, 1975).

- German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936) conceived the terms Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft in his influential work Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887). His theory distinguishes between Gemeinschaft (community), comprised of personal and in-person ties defined and maintained by traditional social rules, and Gesellschaft (society), which is typified by impersonal and indirect ties as a result of being part of a larger, more individualistic, more industrialized society where social relationships are structured in the interest of efficiency or economic or political factors.

- A school of thought according to which each of the institutions, relationships, roles, and norms that together constitute a society serves a purpose, and each is indispensable for the continued existence of the others and of society as a whole. When some part of an integrated social system changes, a tension between this and other parts of the system is created, which will be resolved by the adaptive change of the other parts (Britannica, n.d. b). A criticism of this framework is that it tends to remove the humanity of humanity from the lens: human agency; needs; emotions etc. are not taken into account.

- Ideal types does not mean idealistic in the sense of “good”. Rather, as developed by Max Weber (1904, cited by Swedberg, 2018, p.181), it is a comparative analytical methodology that describes a deliberately exaggerated reality by accentuating – or stating a series of – characteristics; actual reality might fulfil some of the criteria but will very likely be more complex than the simplified example. In this way, to describe ideal types is to illustrate extreme – and, in this case, polarized – examples that remove the complications of the idiosyncrasies of actual reality. Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft theory, for example, concerns two ideal types.

- Turner was yet to conceive of liminoidity – his paper on communitas was written in 1969, but his distinctions between liminal and liminoid were not written until 1974.

- Small (1998) theorizes that the value of music lies within the relationships that are formed in its creation and that participants enact ‘ideal relationships’ (p.13) through musicking.

- First published in 1990, Sound Sense UK’s Sounding Board journals were ‘one of the first publication platforms dedicated solely to community music’ (Humphrey, 2020, p.40).

References

Adkins, B., Bartleet, B.-L., Brown, A. R., Foster, A., Hirche, K., Procopis, B., Ruthmann, A., and Sunderland, N. (2012). Music as a tool for social transformation: A dedication to the life and work of Steve Dillon (20 March 1953-1 April 2012). International Journal of Community Music, 5(2), 189-208.

Boeskov, K. (2017). The community music practice as cultural performance: Foundations for a community music theory of social transformation. International Journal of Community Music, 10(1), 85-99.

Britannica (n.d. a). Mechanical and organic solidarity. In Britannica.com encyclopaedia. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/mechanical-and-organic-solidarity

Britannica (n.d. b). Structural functionalism. In Britannica.com encyclopaedia. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/structural-functionalism

Britannica (n.d. c). Émile Durkheim. In Britannica.com encyclopaedia. Retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Emile-Durkheim

Brøske, B. Å. (2017). The Norwegian Academy of Music and the Lebanon Project: The challenges of establishing a community music project when working with Palestinian refugees in South Lebanon. International Journal of Community Music, 10(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.10.1.71_1

Currie, R., Gibson, J., and Lam, C. Y. (2020). Community music as intervention: Three doctoral researchers consider intervention from their different contexts. International Journal of Community Music, 13(2), 187-206.

Deane, K. (2018). Community music in the United Kingdom: Politics or Policies?. In B.-L. Bartleet and L. Higgins (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Community Music (pp. 323-342). Oxford University Press.

Dunphy, K. (2018). Theorising arts participation as a social change mechanism. In B.-L. Bartleet and L. Higgins (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Community Music (pp. 301-321). Oxford University Press.

Durkheim. É. (2010). From Mechanical to Organic Solidarity. In A. Giddens and P. Sutton (Eds.), Sociology: Introductory readings, (3rd ed., pp. 25-29). Polity Press.

Gibson, J. (2020). Making Music Together: The community musician’s role in music-making with participants. [Doctoral dissertation, York St John University].

Graburn, N. (1978). Tourism: The Sacred Journey. In: Y. Smith (Ed.), Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism (pp. 21-36). Blackwell.

Graves, J. (2010). Cultural democracy: The arts, community, and the public purpose. University of Illinois Press.

Hayes, C. J. (2008). Community music and the GLBT chorus. International Journal of Community Music, 1(1), 63-67.

Helsel, P.B. (2009). Liminality in Death Care: The Grief-Work of Pastors. Journal of Pastoral Care Counsel. 63(3-4), 1-8.

Henley, J., and Parks, J. (2020). The pedagogy of a prison and community music programme: Spaces for conflict and safety. International Journal of Community Music, 13(1), 7-27.

Higgins, L. (2008). Growth, pathways and groundwork: Community music in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Community Music, 1(1), 23-37.

Higgins, L. (2012). Community Music: In Theory and In Practice. Oxford University Press.

Higgins, L. (2015). Hospitable music making. In C. Benedict, P. Schmidt, G. Spruce, and P. Woodford (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Social Justice in Music Education (pp. 446-455). Oxford University Press.

Higgins, L. D. (2006). Boundary-walkers: Contexts and concepts of community music. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Limerick]. http://blogs.bu.edu/higginsl/files/2010/01/Boundary-Walkers-Lee-Higgins-PhD-2006.pdf

Howell, G., Pruitt, L., and Hassler, L. (2019). Making music in divided cities: Transforming the ethnoscape. International Journal of Community Music, 12(3), 331-348.

Humphrey, R. (2020). A critical discourse analysis of the Sounding Board journals: Examining the concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation in community music discourse. Transform, 1(2), 39-60.

Intellectbooks.com (n.d.). International Journal of Community Music. https://www.intellectbooks.com/international-journal-of-community-music

Kelly, O. (1984). Community, Art and the State: Storming the Citadels. Comedia Publishing Group.

Kertzer, D.I. (2019). Introduction. In The Rites of Passage (2nd ed., pp. vii-xliv). The University of Chicago Press.

Lee, R. (2010). Music Education in Prisons: A Historical Overview. International Journal of Community Music, 3(1), 7–18.

Mackay Yarnal, C. (2006). The Red Hat Society: Exploring the Role of Play, Liminality, and Communitas in Older Women’s Lives. Journal of Women Aging, 18(3), 51-73.

Phelan, H. (2008). Practice, Ritual and Community Music: Doing as Identity. International Journal of Community Music, 1(2), 143–158.

Reed-Danahay, D. (2020). Brexit, Liminality, and Ambiguities of Belonging: French Citizens in London. Ethnologia Europaea, 50(2), 16-31.

Routledge Companion Websites (2012a, December 12th). Performance Studies: An Introduction – Liminal and Liminoid [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dygFtTWyEGM&ab_channel=CompanionWebsites

Routledge Companion Websites (2012b, December 17th). Performance Studies: An Introduction – Victor Turner’s Social Drama [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pnsw5xFuXHE&ab_channel=CompanionWebsites

Rumelili, B. (2003). Liminality and the Perpetuation of Conflicts: Turkish-Greek Relations in the Context of Community-Building by the EU. European Journal of International Relations, 9(2), 213-248.

Sandstedt, E. and Westin, S. (2015). Beyond Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. Cohousing Life in Contemporary Sweden. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(2), 131-150.

Schippers, H. and Bartleet, B.-L. (2013). The nine domains of community music: Exploring the crossroads of formal and informal music education. International Journal of Music Education. 31(4). 454-471.

Sheridan, M. and Byrne, C. (2018). Transformations and cultural change in Scottish music education: Historical perspectives and contemporary solutions. International Journal of Community Music, 11(1), 55–69.

Shiloh, C. J., and Lagasse, A. B. (2014). Sensory Friendly Concerts: A community music therapy initiative to promote Neurodiversity. International Journal of Community Music, 7(1), 113-128.

Small, C. (1998). Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Smilde, R. (2010). Lifelong and lifewide learning from a biographical perspective: transformation and transition when coping with performance anxiety. International Journal of Community Music, 3(2), 185-202.

Söderlund, J. and Borg, E. (2017) Liminality in Management and Organization Studies: Process, Position and Place. International Journal of Management Reviews. 20(4), 880-902.

Spiegel, A. D. (2011). Categorical difference versus continuum: Rethinking Turner’s liminal-liminoid distinction. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(1-2), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2011.11500004

Sunderland, N., Graham, P., and Lenette, C. (2016). Epistemic communities: Extending the social justice outcomes of community music for asylum seekers and refugees in Australia. International Journal of Community Music, 9(3), 223-241.

Turner, V. (1974). Liminal to liminoid, in play, flow, and ritual: An essay in comparative symbology. Rice Institute Pamphlet-Rice University Studies, 60(3), 53-92.

Turner, V. (1975). Revelation and divination in Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.

Turner, V. (1985). Liminality, Kabbalah, and the media. Religion, 15(3), 205-217.

Turner, V. (2017). Liminality and Communitas. In The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (pp. 94-130). Routledge. (1969)

Van Gennep, A. (1960). The Rites of Passage (M.B. Vizedom and G.L. Caffee, Trans.). Routledge and Kegan Paul. (1909).

Van Gennep, A. (2019). The Rites of Passage (2nd ed.). The University of Chicago Press. (1909)

Veblen, K. K. (2008). The many ways of community music. International Journal of Community Music, 1(1), 5–21.

Veblen, K. K., Elliott, D. J., Messenger, S. J., and Silverman, M. (Eds.). (2013). Community music today. Rowman and Littlefield.

Versteeg, P. G. A. (2011). Liminoid religion: Ritual practice in alternative spirituality in the Netherlands. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(1-2), 5-10.

Wels, H., Van Der Waal, K., Spiegel, A., and Kamsteeg, F. (2011). Victor Turner and liminality: An introduction. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(1-2), 1-4