Humphrey, R. (2020) Download PDF

York St. John University, UK

ryan.humphrey@yorksj.ac.uk

Abstract:

Language plays a vital role in shaping our actions and understanding of the world. Scholars refer to the interaction of language and action under the heading of ‘discourse’, a feature within all practices. Community music as a field of scholarship and practice is nuanced and diverse and, as such, so is our discourse. As practitioners and researchers, we may find ourselves using terms and phrases with little understanding of how these terms have been used within our discourse. Recognising that the concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation have become commonly drawn upon in community music literature, this article outlines a critical discourse analysis of Sound Sense UK’s Sounding Board journals, which examines how these three concepts have been used in community music discourse in the UK, alongside possible implications for practice. The Sounding Board journals were one of the first publication platforms dedicated solely to community music. Since they were first published in 1990, they have played a crucial role in supporting the development of the field, providing a platform to share the latest reports on projects and research. As a step towards deconstructing the language in community music discourse, it is hoped that this article may influence researchers and practitioners to analyse their language when writing critically about community music.

Keywords: ownership, empowerment, transformation, critical discourse analysis, policy and well-being

Introduction:

Language plays an integral and influencing role in our lives. The terms or phrases that we use can shape our actions, how we make sense of the world, and our identities. James Paul Gee (2014), a leading expert in the field of linguistics, frames the synergy of language and action under the heading of ‘discourse’, a feature embedded within our everyday practices. As a field of scholarship and practice, community music is nuanced and diverse and, as a result, so is the language that we choose to use, and therefore our discourse. As researchers and practitioners, we may often find ourselves using terms or phrases to describe elements of community music practice, without any clear theoretical underpinning or understanding of how these concepts have come into operation within our discourse. With this in mind, this article aims to address how three concepts that are commonly drawn upon within community music literature, have become operationalised within community music discourse, and the effects that this may have on practice.

The concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation are chosen for examination through this study as they are extensively drawn upon as critical facets of the work of community musicians. For instance, Kathryn Deane and Phil Mullen (2018) propose that enabling young people living in challenging circumstances to experience a sense of ownership through the music-making process could elicit an empowering experience that may lead to personal transformations in the young person’s levels of self-confidence or self-esteem. Likewise, Tim Joss (1994) highlights empowerment as a critical element to the work of community musicians, which can only be achieved through listening to the community, thus enabling the occurrence of social change for groups and individuals. Although these concepts are often drawn upon in community music literature, there has been little exploration of how these terms have been used within community music discourse and how these concepts may have developed and changed. This article aims to develop a historical perspective on how the concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation have been used in community music discourse in the United Kingdom by outlining a critical discourse analysis based on an in-depth examination of the Sounding Board journals.

The Sounding Board journals were first published in 1990, following the establishment of the United Kingdom’s first and only professional association for community musicians, Sound Sense, in 1989. Sound Sense was established due to the increasing number of individuals delivering, organising or engaging in participatory music-making. It was hoped that providing an umbrella organisation for community musicians could provide support and guidance around best practice for practitioners on the ground (Everitt 1997: 96). The journals are one of the ways Sound Sense supports the dissemination of practice across the field through housing within them a range of material to support community musicians, including: articles detailing specific projects and approaches to music-making, the latest research projects being undertaken within community music, and details of training events and professional development training opportunities. Many of the articles are written by community musicians themselves, or by board members of Sound Sense.

Guiding this analysis are two primary questions:

- How have the concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation been shaped within the discourse of community music?

- What has been the political implication of this, and what has been its effects regarding the development of practice?

In order to undertake a critical discourse analysis, it was necessary to develop a theoretical framework to explore the ideas surrounding each of these three concepts and how they may work in synergy.

Ownership-Theoretical Conceptions:

Based on the studies examined, the following three theoretical elements are seen as being critical to the concept of ownership:

- Self-ownership: Enabling an individual to gain the ability to make critical decisions and achieve a sense of control (Cohen 1978).

- Ownership as a means to freedom: Individuals can live without interference within society through claiming a sense of ownership (Russell 2018).

- Ownership as a means to a sense of democracy: Enabling individuals to have a say in areas that matter most to them through fostering a sense of control (Dewey [1916] 2018).

Ownership is intrinsically linked to ideas of control, specifically how it can elicit opportunities for individuals to make critical decisions and feel that they have the ability and rights to participate in society. Individuals gain this sense of control from being able to either have a physical property which they can make decisions over or through feeling that their beliefs and views are being acknowledged and accepted by others (Cohen 1978; Russell 2018). For minority or oppressed communities, this can be integral for helping them to integrate into the community, without concerns of interference or marginalisation by others (Castles 2014).

Empowerment-Theoretical Conceptions:

Based on the studies examined, the following three theoretical elements can be viewed as critical to the concept of empowerment:

- Empowerment within psychology: Specifically, the empowerment model that highlights the areas self-efficacy, competence and knowledge as being critical for fostering an empowering process (Cattaneo & Chapman 2010).

- Power relations: The idea that through examining the different power relations a group may face in society, ideas may be formed on how to gain equal power status (Thompson 2007).

- Social Work theories of empowerment: Fostering an empowering process is critical within social work practice (Lynch 2016: 376).

Individuals must be supported in making their own decisions on the goals they would like to achieve and the process to take towards achieving these goals in order to enable an empowering process (Lynch 2016; Freire [1969] 2011). These goals may be personal to an individual or may be related to making changes in broader society. Having the opportunity to make changes relies on individuals feeling as if they have a sense of power, which they can gain from being supported by the work of community development projects, social workers or through finding a network of individuals that share similar views or experiences (Cattaneo & Chapman 2010).

Transformation-Theoretical Conceptions:

The term ‘transformation’ has become synonymous with change both at individual and society level. Studies exploring transformation often draw on the following areas:

- Transformative participation: Where engaging in groups or activities is seen as affecting an individual’s outlook on society, or on how they might see themselves (White 1996).

- Social Transformation: Where a group or individual’s social status is affected and changed within the community they live in (Castles 2014).

- Transformational experiences: The idea that engaging in everyday activities can offer individuals an epistemically (developing subject-specific knowledge) or personally (developing subjective and individual knowledge) transformational experiences (Paul 2014).

Transformation appears as an essential notion for describing a change in how individuals perceive themselves, or how they are viewed in society (White 1996). Often the way that others perceive individuals can support or hinder a transformation. If an individual can build a support network of like-minded individuals, they are likely to feel supported and thus more likely to change their perception of themselves (Paul 2014). Through achieving social transformation, individuals and groups facing oppression can further engage within society and begin to have their voices heard, and ultimately their identity accounted for (Castles 2014).

Construction of Theoretical Framework:

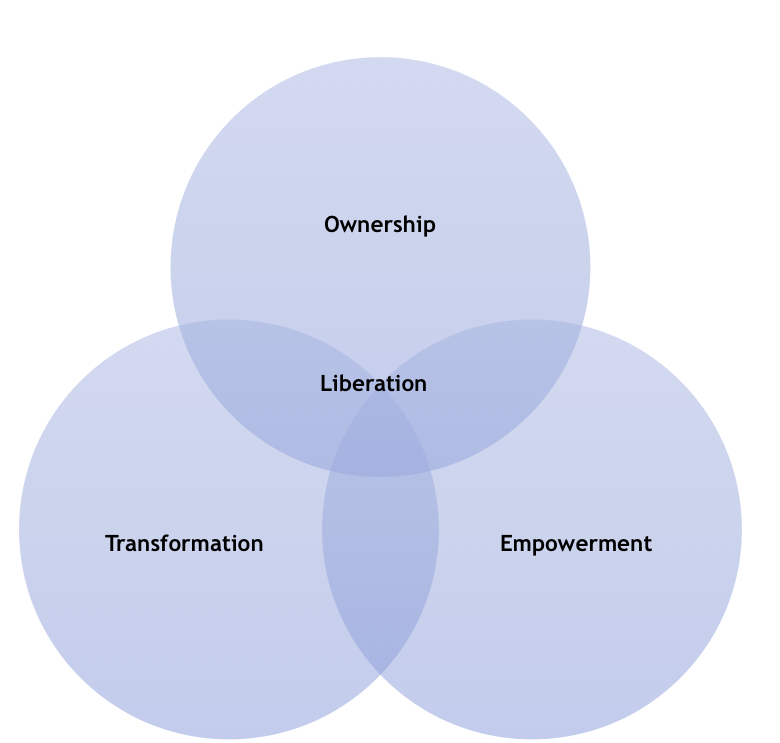

Through building the conceptual dimensions of ownership, empowerment and transformation, it could be argued that at the intersection of these three concepts lies the idea of liberation (see figure 1.1) which is used to guide the analysis of the Sounding Board journals.

Figure 1.1: Theoretical Lens of Ownership, Empowerment and Transformation.

All three concepts highlight how ownership, empowerment, and transformation may work in synergy to develop a liberating experience. The conceptual dimension of ownership, for instance, highlights how being able to claim something as owned, embeds a sense of freedom for individuals. This resonates with Freire’s ([1969] 2011) conceptualisation of how to develop a liberating learning experience; groups must be able to take a stake of ownership through making critical decisions on the process.

Similarly, empowerment’s conceptual dimension houses ideas of overcoming oppression and striving for freedom through having the opportunity to set meaningful goals and take action. Lauren Bennett Cattaneo & Aliya Chapman (2010) argue that being able to set meaningful goals and make decisions on the course of action to be taken in order to achieve these goals, can increase an individual’s self-efficacy and provide an empowering and liberating experience. For example, scholars exploring feminist theory have engaged with these ideas, highlighting, for instance, how supporting women to explore their oppression in society, and then enabling them to decide on the best course of action to take to overcome the oppression, can be empowering and liberating (Carey, Dickinson & Cox, 2018; Komter, 1991).

Transformation also houses ideas of liberation. The idea of a liberating experience is built on the ideals of groups achieving social change for themselves (Freire [1969] 2011; Cattaneo & Chapman 2010). Examining how engaging in community development projects may support communities through a socially transformational experience, Ledwith (1997) proposes that supporting communities to take leadership roles and make critical decisions on a project can be critical for eliciting a liberating experience. Engaging within a community-led project can enable participants to build support networks and begin working towards change that may be personal or social. By understanding how these three concepts work in synergy, it can be argued that the idea of liberation appears as a critical element, and that through developing this framework we can use this as a lens through which to examine these three concepts within the Sounding Board journals.

Methods:

To examine how these three concepts have been used within community music discourse, a critical discourse analysis approach is utilised. Gee (2014), describes critical discourse analysis as an approach to analysing ‘how language forms correlations at the utterance type level, and how situated meanings are associated with social practices and broader social and political institutions’ (Gee 2014: 86). As an approach, critical discourse analysis has been viewed as a way of examining power at play in society, highlighting specific areas where there may be social injustice, power hierarchy, and unequal class relations (Fairclough 2001).

Norman Fairclough (2001), an expert in linguistics, proposes a three-step approach to undertaking a critical discourse analysis:

- Textual level: Examination of the text and the way that sentences and words are being used.

- Discursive Practice level: Examination of how the text is setting specific ways of viewing ideas and how this may be interpreted.

- Social Practice level: Examination of how the text is influenced and influences the broader social and political institutions and the effect that this has upon the social practice.

(Fairclough 2001)

Through utilising Fairclough’s (2001) three-step approach, it was anticipated that insights could be gained into how these three concepts have been used within community music discourse and how any of these changes may relate to broader social and political events.

The Sounding Board journals were chosen for analysis as they were one of the first publications specialising in community music with the United Kingdom. The journals played a critical role in supporting the development of the field through housing the latest reports on projects, and research and development within the field of community music. Although the Sounding Board journals do not require a peer review process, they provide an invaluable resource for community music practitioners. Practitioner based journals focus more on the practical implications for their audience of what is being explored, with little emphasis on the research methods and theoretical landscape of the study (Emerald publishing, 2020).

Sixty-five of the Sounding Board journals were analysed across the years 1990-2020 using Fairclough’s (2001) three-step approach. The analysis began at the textual and discursive level (Fairclough 2001) by examining the language used to describe aspects of community music practice. A set of keywords (see figure 1.2) emerging from the theoretical framework were used to guide the analysis at this stage.

| The Keywords derived from the theoretical framework | ||

| Ownership: | Empowerment: | Transformation: |

| Decision-making | Voice acknowledgement | Social Cohesion |

| Freedom | Support Network | Changing social status |

| Agency | Meaningful Goals | Changing perception |

| Choice | Control | Self-confidence |

| Interests | Power | Self-esteem |

| Expression | Motivation | Increased enjoyment |

Figure 1.2: Keywords table derived from the theoretical framework

Early editions of Sounding Board (1990-2010) were not digitised; therefore, each edition had to be examined in its entirety with no option of searching for keywords. Each article was read, and articles discussing ownership, empowerment and transformation were noted. These articles were then re-examined, explicitly searching for the keywords (see figure 1.2) or other phrases or terms with possible relevance to the three concepts and community music practice. A similar process was undertaken for digitised articles. Keywords from each concept were digitally searched. Each article was noted, in addition to the terms or phrases being used. Where other potentially relevant words or phrases emerged, I used my interpretation of the three concepts, and knowledge of the field, to decide on whether or not to include these terms in the analysis. Fairclough (2001) and Gee (2014) argue that interpretation is a key element, within critical discourse analysis, in assessing how the use of language within a text relates to broader political and social events. Researchers will always bring with them a particular viewpoint or interpretation that will shape their view of the language that is used, and its meaning, due to their engagement in specific social practices or social groups (Gee, 2014: 86). In this research, interpretation played a critical role in several areas, from interpreting which articles addressed each concept to using my knowledge of the field to hypothesise why the use of these three concepts may have changed.

Once analysis had been completed at the textual and discursive practice levels, the methodology was used to undertake analysis at the social practice level, examining how the broader social and political structures may have influenced the development of the discourse. Fairclough (2001) proposes that this is a critical stage in the analysis process for developing knowledge of the different power structures at play within society and how that can affect a field’s discourse. Fairclough (2010) writes that, at this stage of the analysis, the researcher must use their knowledge of the field of social practice to thoroughly examine the reasons why the discourse may have changed or developed. The next section will begin by highlighting the findings of the analysis at Fairclough’s (2001) textual and discursive level before then applying these findings at the social level.

Findings at Textual and Discursive Level:

Ownership:

The concept of ownership is used in several ways within the Sounding Board journals. Providing opportunities for groups to make critical decisions and have choices regarding either the project, process, or genre of music appeared to play a critical role in enabling a sense of ownership to flourish within music projects. John Stevens’s (1991) article ‘The Sounding Board Interview’ suggests that the role of the facilitator is to work with the participants’ choice of activity, rather than proceeding with a predetermined plan (Stevens 1991:7). Stevens believed that offering a sense of ownership through decision-making opportunities could strengthen participant engagement. This was seen as critical, particularly for groups labelled as being ‘hard to reach’ or ‘facing challenging circumstances’ and who may otherwise have struggled to engage in the music-making process.

This idea of providing a sense of ownership through decision-making and a sense of control remained prominent throughout the exploration of the Sounding Board journals. However, in later editions, the implications of fostering a sense of ownership were seen to be far greater than merely helping groups to engage. Ownership, and the opportunity to have a sense of control within the creative process, seemed to play a vital role in enabling a sense of creative freedom, which was critical in helping individuals to overcome mental health issues. For example, the article ‘Looking at them, Looking at us’ (Sounding Board 2001) describes how enabling individuals with mental health issues to experience a sense of creative freedom supported them in finding a form of control within their lives. Individuals were supported by music facilitators in the establishment and running of projects, enabling participants to feel a sense of control and ownership within the work. For members of the project discussed in the article, the sense of control was a significant first step in helping them to feel that they could make changes within their lives. One of the most common activities deemed as providing a sense of ownership was song-writing. Several articles described song-writing as a fundamental way of helping participants to express both their own identity and that of their cultural heritage. The article ‘Music on The Front Line’ (Sounding Board 2001) described how supporting ethnic groups to explore and create songs that may link to their cultural identity can be a useful tool for helping them to overcome oppression that they may face from mainstream culture.

Empowerment:

In other articles, finding a way for groups to express themselves was seen as a critical step for instilling an empowering process. For example, the article ‘A Captive Audience’ by Katie Tearle (1993) describes how supporting male prisoners to express their experiences to others through music, supported an empowering process that helped participants to feel as if they were being recognised as individuals, and led to an increase in their self-esteem and self-confidence (Tearle 1993:18-19). This was a critical step for enabling an emotional experience that could help the participants alter their perceptions of themselves through developing new skills and raising their aspirations.

The sense of achievement and motivation that came from developing new skills was also viewed as enabling an empowering process for participants. Community musicians were portrayed, across several articles, as playing a supporting role in providing support for participants to build the skills they wanted. For instance, Siggy Patchitt’s article ‘Inclusion: Starting a Revolution’ (2017) suggests that a critical step towards working inclusively with people is about recognising the goals that they want to achieve and then supporting them to achieve those aims whether it be personal, spiritual, or physical aspects of their lives (Patchitt 2017: 8). Similarly, Kathryn Deane’s article ‘Challenging Behaviour’ (2003) also describes how supporting young people labelled as being difficult or distressed to engage in music-making enabled them to overcome the challenges they faced through building new skills that ultimately led to them experience higher self-esteem (Deane 2003: 19). Although there was no specific activity labelled as providing the best means of enabling an empowering process, many articles drew on the idea that enabling opportunities for music-making elicits a unique and empowering experience. Furthermore, the opportunities for decision-making and control within the process were also viewed as crucial to fostering a sense of power for individuals (Northcotte 2018: 9-10).

Transformation:

There are several ways that the concept of transformation is used within the Sounding Board journals. In the early years of publication, articles emphasised how engaging with community music could often provide a means of bringing culturally diverse communities together, aiding social cohesion and, ultimately, creating a sense of social transformation. For example, ‘More Music in Morecambe’ (1994) describes how ‘More Music’ aimed to bring communities together and support Morecambe’s residents to develop their confidence and power in order to aid the redevelopment of Morecambe (Sounding Board 1994: 24). It was anticipated that this would be the first step in helping to transform the town into the tourist destination that it had once been in the late 1960s, bringing with it a new avenue of much-needed employment to the local economy. Through working together, it was hoped that a stronger sense of community could be formed within the town(1).

Although the idea of bringing communities together through music-making was still perceived as an outcome of community music work in the later years, the term ‘social inclusion’ began to gain popularity at the start of the new millennium. Sound Sense’s article ‘Music for a Changing World’ (Sounding Board 2000) highlights ‘governments, funders, movers and shakers in health, social welfare, lifelong learning and community development organisations’ belief that community music can bring communities together and aid social inclusion’ (Sounding Board 2000:13). Since then, the term has gained a significant presence within the Sounding Board journals for describing social and cultural transformations.

In more recent years, articles in Sounding Board began to focus more on ideas of music-making as an aid towards improved self-perception, health and well-being. Anita Holford’s (2019) article addressing music-making with teenagers suffering from mental health issues, and ‘Hidden Voices’ (Sounding Board, 2020), an article addressing music-making with carers, both suggest that through music-making, participants were able to find a way to overcome or improve their mental health issues. Holford (2019) suggests that engaging in music-making became a coping strategy that brought about a sense of relaxation and mindfulness (8). Likewise, ‘Hidden Voices’ suggests that engaging in music-making will support the development of the carers’ positive image through a creative, person-centred and inclusive song-writing process (Sounding Board 2020:4). The next section will discuss the findings through Fairclough’s (2001) social practice lens, whereby the use of these three concepts can be examined in relation to social and political events.

Discussion at the Social Level:

Through analysing the Sounding Board journals at the social level, we can begin to draw ideas together as to how the concepts of ownership, empowerment and transformation have been used in the last thirty years within community music discourse, and how changes within their usage may relate to broader social and political policies. There are evident changes within the Sounding Board discourse that coincide with changes in political policy, particularly concerning the perception of the arts in society.

For instance, in the inaugural issue of Sounding Board, the concept of ownership was used throughout several articles as a way of providing participants with a sense of control in the music-making process. Authors such as John Stevens (1991) proposed that offering opportunities for ownership and control could elicit a more meaningful and engaging musical experience for participants. Stevens saw this as critical for sustaining participants’ engagement in the project and ensuring that their voices were being heard and acknowledged. Alison Jeffers and Gerri Moriarty (2018) write that community arts practice, including community music, had always centred around supporting participants to gain a sense of ownership within the process by enabling them to have their voices heard. This could be critical for supporting groups during the British community arts movement(2) to feel a sense of power, something that many of the communities engaging in arts projects appeared to lack (Jeffers and Moriarty 2018).

However, by the late 1990s, ideas of ownership shifted, with articles drawing on ownership as a critical element within approaches to working with participants, particularly young people, who were often viewed as hard to reach and facing challenging circumstances (Sounding Board 1998:7; Sounding Board 2000). For instance, John Stafford, Elaine Whitewood and Tim Fleming (2007) outline how enabling children in the care system to make critical decisions and fostering a sense of ownership within the music-making process could be crucial to engaging the children from the outset. They suggest this helps them to develop various personal skills such as increased self-confidence and self-esteem. Similarly, Alex Pitt (2003) writes how enabling young people at risk of becoming involved in crime to make decisions concerning the running of a project could be a tool for increasing individuals’ engagement in learning, as the project would be centred around their interests. Pitt writes that this appears to be integral to supporting participants to be drawn away from the risk of criminal involvement. Thus, creating a sense of ownership was viewed as an essential element in offering a music-making experience that could be personally impactful.

This change in perception, from recognising the concept of ownership as a tool for engagement towards being a way of eliciting personal impacts, showcases one way that the discourse within community music has changed. Several researchers in the field of community music and community arts have drawn on the late 1990s as a critical period within which the perception of the role of the arts in society began to change and, as such, introduced new conversations about the potential impact of the arts (Hope 2011; Jeffers and Moriarty 2018).

By 1997, the United Kingdom’s political landscape was changed; the New Labour government fronted by Tony Blair was elected, removing a conservative government that had been in power since 1974. As part of its new manifesto, Labour brought with it a new perception of the role of the arts in society, recognising its potential to be economically and socially impactful (Jeffers & Moriarty 2018). The idea of conceiving the arts as socially impactful lent itself to Labour’s new social inclusion policy, fuelled by a neoliberal agenda. This emphasised individual freedom and personal health and well-being, and opened the door for the emergence of a new discourse within the arts.

The change in community music discourse is recognised by Deane (2018) who writes that community music became further depoliticised in the late 1990s, removing itself from its roots as a form of social activism within the community arts movement. Instead, community musicians and community artists began to work with funders and political bodies, developing work targeted at specific groups in society who were viewed as marginalised or oppressed, and who were at the heart of the government’s social inclusion agenda. Community arts researcher, Charlotte Sophie Hope (2011), proposes that in some ways this new interaction led to community arts becoming a form of ‘socially engaged arts’ that resulted in community artists delivering work that was no longer being created by the community. Instead, the work was commissioned against a set backdrop of predetermined outcomes and targets, often with specific social aims at its core, with little involvement from the community in the planning stages.

Changing perceptions of the role of the arts in society, and how projects were being delivered, impacted on how the concept of transformation was now being utilised in community music discourse. For example, the concept of transformation within early editions of the Sounding Board journal was based around the idea of bringing communities together through active multi-cultural music-making (Sounding Board 1996) enabling communities to gain a sense of social cohesion. For some groups, addressing this was crucial in helping them to enhance participation within their communities. However, in later editions of Sounding Board, the concept of transformation became more aligned with the personal and individual transformations that engaging in community music might lead to for individuals, particularly concerning their health and well-being. For instance, Holford (2019) suggests that engaging in music-making has a positive effect on teenagers suffering from mental health difficulties by helping them to perceive themselves in a more positive light.

Within these examples relating to the concepts of ownership and transformation, it is clear that the discourse surrounding community music became more focused on the health and well-being agenda that was at the crux of the Labour government’s policies. This was further emphasised through Labour’s work in rebranding Arts Council England and developing Youth Music (1999), both of which focused on the social impacts of the arts. If community music was to continue to grow and become an integral part of society, then the facilitators, musicians and organisations had to ensure that they were enacting the social practice and discourse that would open the doors of funding and possibility. Thus, the discourse and focus of community music had to change to become more centred on the outcomes and impacts for individual health and well-being.

This reasoning also encapsulates why the use of the term ‘empowerment’ seems to have remained mostly unchanged within the United Kingdom’s community music discourse. The concept of empowerment always appears to be connected to ideas of supporting individuals in developing their self-confidence, support networks, and critical skills through musical engagement (Tearle 1993; Stevens 2006). These person-centred outcomes are drawn upon extensively in Cattaneo and Chapman’s (2010) empowerment model.

Conclusion:

Community music discourse appears to have changed its focus over the last thirty years following the influence of the broader social and political bodies who fund and govern much of community music’s work. Instead of being used to describe the effects that engaging in music-making may be have on groups or communities, the discourse has now been repositioned towards a more individual and person-centred focus. The terms ‘ownership’, ‘empowerment’ and ‘transformation’, can be used as critical indicators for tracing and highlighting these changes within the field. Understanding how and why our discourse is developing is critical for ensuring that we as researchers, practitioners or funders know how and where our practice is situated within broader cultural and political contexts, and how these contexts are continuously shaping it. Further discourse analysis on other publication platforms would be necessary to gain a broader understanding of how the discourse may have changed and developed in the field in general. As a step towards deconstructing the language and discourse surrounding community music, it is hoped that this article may influence others to critically analyse their language when writing about and describing community music.

Endnotes:

(1) More Music is a music and education charity based in Morecambe, United Kingdom, that was established in 1993 by Pete Moser. Further details of the charity can be found here: https://moremusic.org.uk/about-more-music/

(2) The British Community Arts Movement was a political movement emerging in the late 1960s that aimed to challenge the distribution of cultural goods and artistic conformity, emphasising the idea of ‘art’ instead as a human right.

References:

Carey, G., Dickinson, H. & Cox, E.M. (2018), ‘Feminism, gender and power relations in policy – starting a conversation’, Australian Journal of Public Administration: 77 (4), pp.519-524.

Castles, S. (2014), Social Transformation and Migration: National and Local Experiences in South Korea, Turkey, Mexico and Australia, New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Cattaneo, L. B. & Chapman, A. (2010), ‘The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice’, American Psychologist: 65 (7) pp. 646-59.

Cohen, G. A. (1978), Self-Ownership, Freedom and Equality, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Deane, K. (2003), ‘Challenging behaviour’, Sounding Board, Winter 2003, p. 19.

Dewey, J. ([1916] 2018), Democracy & Education, Great Britain: Penguin Publications.

Emerald Publishing (2020), How To…Write for a Practitioner Audience, https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/archived/authors/guides/write/practitioner.htm. Accessed 11 September 2020.

Everitt, A. (1997), Joining in: An Investigation into Participatory Music, London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Fairclough, N. (2001), Language and Power 2nd ed., Harlow: Routledge.

Freire, P. ([1968] 2017), Pedagogy of the Oppressed, London: Penguin Modern Classics.

Gee, J.P. (2014), An introduction to Discourse Analysis 3rd ed., New York: Routledge.

Hope, C.S. (2011), Participating in the wrong way? Practice Based Research into Cultural Democracy and The Commissioning Arts Effect Social Change, https://sophiehope.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/SH_PhD_Final.pdf. Accessed 9 August 2020.

Holford, A. (2019), ‘Music mins: Music-based mental health work with teenagers’, Sounding Board: 19 (1) pp. 8-9.

Jeffers, A. & Moriarty, G. (2017), Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement, London: Bloomsbury.

Joss, T. (1994), The Seminar Report, https://www.isme-commissions.org/uploads/1/1/4/9/114996981/1994_the_role_of_community_music_in_a_changing_world_1994.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2020.

Komter, A. (1991), ‘Gender, power and feminist theory’ in K. Davis, M. Leijenaar, & J. Oldersma (eds), The Gender of Power, London: Sage Publications, Inc, pp. 42-62.

Ledwith, M. (1997), Participating in Transformation, Birmingham: Venture Press.

Lynch, M. (2016), ‘Re-working empowerment as a theory of practice’, Qualitative Social Work: 17 (3) pp. 373-86.

Mullen, P. & Deane, K. (2018), ‘Strategic working with young people facing challenging circumstances’ in B.L. Bartleet & L. Higgins (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 177-195.

Northcotte, S. (2018), ‘Edinburgh’s Inspire Project-what makes us tick’, Sounding Board: 18 (2&3) pp. 8-9.

Patchitt, S. (2017), ‘Inclusion: Starting a revolution’, Sounding Board: 17 (3&4) pp. 8-9.

Paul, L.A. (2014), Transformative Experiences, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pitt, A. (2013), ‘Reducing crime the music way’, Sounding Board: Winter 2003, pp. 10-13.

Russell, D.C. (2018), ‘Self-ownership as a form of ownership’ in D. Schmidtz & C. E. Pavel, The Oxford Handbook of Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 21-40.

Sounding Board (1993), ‘Firing ahead’, Sounding Board: Summer 1993, pp. 12-13.

Sounding Board (1994), ‘More Music in Morecambe’, Sounding Board: Autumn 1993, pp. 24-25

Sounding Board (1996), ‘Cut and blend’, Sounding Board: Spring 1996, pp. 5-6.

Sounding Board (2000), ‘Music for a changing world’, Sounding Board: Winter 2000, pp. 13-15.

Sounding Board (2001) ‘Looking at them, looking at us’, Sounding Board: Summer 2001, p. 9.

Sounding Board (2001), ‘Music on the front line’, Sounding Board: Summer 2001, pp. 12-15.

Sounding Board (2020), ‘Hidden Voices programme to support social connectedness for female carers in Birmingham’, Sounding Board: 19 (3&4), pp. 4-5.

Stevens, J. (1991), ‘The Sounding Board interview’, Sounding Board: Winter 1991, pp. 6-7.

Tearle, K. (1993), ‘A captive audience’, Sounding Board: Autumn 1993, pp. 18-19.

Thompson, N. (2007), Power and Empowerment, Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing LTD.

White, S. (1996), ‘Depoliticising development: The uses and abuses of participation’, Development in Practice: 6 (1) pp. 6-15.