Kinnunen, C. (2024) – Download PDF – pp. 122-139

Wilfrid Laurier University

Email: kinn1410@mylaurier.ca

Abstract

Many intersecting roles and identities inform my thinking and approach to research and practice. In addition to being an independent music educator and community musician, this includes (but is not limited to) being a woman in midlife, a parent, a mature student returning to studies and an emerging researcher. This ongoing reflexive self-study begins to untangle the experience of commencing doctoral studies in later life, exploring these interweaving roles and identities in various contexts through an arts-based autoethnographic process pursued for both research purposes and personal wellbeing. Through interrogation of multiple creative modalities used in documenting my lived experience, including a daily journal, a crochet project, music composition and poetry, results weaved together aspects of uncertainty, belonging, ritual, identity and optimism. It has become an ongoing reflexive component of my continued work in doctoral studies. This article looks at the evolution of this process, what has been revealed so far, and my intention for continued use of this arts-based practice to provide an aspect of self-care through creativity as well as ongoing reflexivity in my interconnected work as a music educator and community musician, an emerging researcher and a lifelong learner.

Keywords: Arts-based research; Autoethnography, Reflexivity, Midlife, Identity, Community in Higher Education

Introduction

As a freelance music educator, community musician and lifelong learner, I continually aim to deepen my understanding of my experiences and relationality to and within my research and practice. I look to open up space for mindfulness and continued empathy and hospitality for those I teach and engage with in various community music activities (Higgins and Willingham 2017; Veblen 2007). I am also affected by additional intersecting roles or aspects of my identity that inform my thinking and facilitation approach, including being a woman in midlife, an early-stage doctoral student returning to school in this later period of life and an emerging researcher.

When I began exploring possibilities for doctoral studies in my area of interest, options nearby were limited, and as a parent with children at home, relocating or extensive travelling was not an option. I was accepted as a preparatory student at a university abroad, where I could participate remotely in their doctoral program as I prepared my research proposal. I spent that year taking part in their well-established music education doctoral seminar and several other classes. During that year of preparatory studies, I decided to document my experience with an arts-based self-study project to chronicle the beginning of this next challenging endeavour in midlife. During that initial year, I also noted that my alma mater nearby was launching a new Community Music (CM) Ph.D. program. Now, in the early stages of my research wonderings, I considered which option might best suit both the research focus and overall experience I hoped to have. These considerations would also play into my craft and journaling project.

This reflexive undertaking was not simply personal. Midlife is a busy, challenging and transitional stage for many (Lachman et al. 2015). Women often find themselves negotiating multiple, demanding roles between parenting, elder care, employment and community responsibilities (Danylova et al. 2024; Thomas et al. 2023). My main doctoral research aims to explore the lived experiences of women during the midlife period who are also often managing transitional experiences, including children leaving or returning home, caregiving for ageing parents, career changes or a return to the workforce after time away for parenting, and health matters such as the effects of the menopausal transition, which in some cases can last over a decade (Mosconi 2024; Thomas et al. 2023). Transitions themselves are meaning-making experiences that take place throughout our lives and can have a profound effect on who we are and can be (Bridges and Bridges 2019; Feiler 2021).

As someone in the midst of this stage of life, I wanted to explore how my lived experiences over time were affecting me and my sense of self as an older graduate student (learner/researcher), a music educator and community musician as a second career (teacher/facilitator) and as a musician/composer/creator/maker (artist). Identification is active and social, ‘a process; something that we do’ (Jenkins 2014: 2). I brought these complexities and tensions to the fore through the use of autoethnography and a/r/tography in order to interrogate these many roles and experiences. I used a multi-modal process to work alongside the fluid and ongoing nature of understanding who we are. I hope to unravel and stitch together my knowledge in potentially more engaged and empathetic ways across these identities and contexts. Much like Turner (2017), who discovered in her doctoral journey that the process of creating music allowed her to examine her multiple roles of artist and CM practitioner and that they were far more interconnected than she’d imagined, I found this investigation of my roles and experiences informed and revealed insights that crossed between them, sometimes with tension or friction, sometimes quite fluidly.

Methodology

I approached this study from a social constructivist and interpretivist lens, recognising that my experiences are influenced by my history as well as the contexts I am in, and that my reality is constructed through these experiences, interactions and interpretations (Creswell and Poth 2018). Autoethnography is a way to connect the personal to the cultural (Bochner and Ellis 2016) and as a reflexive exercise alongside my research work (Adams and Herrmann 2023; Etherington 2004; Kara 2020), it allowed me to use my own experiences to explore ideas of expectations, beliefs, values, and practices, all of which relate to this journey as a student, teacher/facilitator, musician, emerging researcher and a woman in midlife. There are blurred lines across these roles in my main doctoral research, including that of insider/outsider, which continue to emerge (Dwyer and Buckle 2009; Holmes 2020).

I chose arts-based research (Kara 2020; Leavy 2018) to document the experience, using the combination of creative practices as ways of knowing. Creative methods can often reflect more of the multiplicity of meanings in contexts and offer mutual reciprocity with research (Kara 2020). I also yearned for something outside of my comfort zone. I selected fibre art (crochet) as an activity that was not rooted in music but was tactile and would have a physical, tangible result (Riley, Corkhill and Morris 2013; Sjöberg and Porko-Hudd 2019). Kara (2020) notes that embodied research can cause us to have experiences that, at times, can be disorienting or even disturbing. I leaned into the ideas of disentangling or unravelling, and stitching together, all as literal and metaphoric. I additionally wanted something separate from technological influence, which I continued to feel exhausted by post-pandemic, both as a student and teacher.

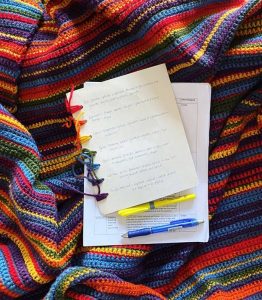

Figure 1.

Alt Text: This image shows two documents – one with yarn colours linked to psychological groupings and a second with journal texts – lying on top of a multicoloured, crocheted blanket.

The project itself was initially inspired by the concept of temperature blankets. I developed a colour guide (Figure 1) and linked it to emotions (rather than to average daily temperatures, as the original idea of temperature blankets would be) alongside more traditional text-based journaling to document the first stage of my doctoral journey. My process for selecting colours was inspired by Goethe’s colour ‘theory’ which suggests colour is linked to phenomena and corresponds to artistic feelings and to the function and psychology of colours, considering ideas of harmony and aesthetics (Goethe 1840/1970: xi). This thinking about how we might link to or assign colours with our own interpretations of our lived experiences or physical spaces in the world offered a sense of freedom in assigning my colour categories. Though I freely selected the colours at the start of the process, I would quickly lose control of how they would emerge as the blanket took shape, each day linking a colour with a corresponding journal entry. The project, therefore, had some basic structure for managing a long-term process of the creative endeavour, which provided some framework but moved out of my control along the way. This dichotomy of feeling control/loss of control in the creation process was sometimes disconcerting, yet it also allowed some level of freedom and ability to relax into the experience.

Further to that process, once I worked through the journal notes and the initial year’s blanket, I felt I was not finished with the reflexive process. I needed to have some way of continuing my exploration and (re)thinking. I added several further creative modalities that would iteratively build on or flow from each other with ongoing reflection in between each step, resulting in a musical work and a poem. The process drew me to a/r/tography as a practice-based research method that ‘recognizes making, learning and knowing as interconnected within the movement of art and pedagogical practices’ (Irwin et al. 2018: 37). This method of living inquiry encourages movement and evolution, a dynamic and entangled approach to consider our interconnected, interleaving roles and identities as artists, researchers and teachers/learners (Irwin et al. 2017; Kara 2020; Springgay et al. 2005). It allowed me to continue processing the experience in a temporal, tactile and reflexive way that permitted deeper emotional and mental experiences and transitions to be revealed over time. As Hesmondhalgh expands on Martha Nussbaum’s Upheavals of Thought, there is a narrative structure to emotions and the arts can help provide us with information we might not access as easily without, and thus may play a major role in our understandings of our selves (Hesmondhalgh 2013: 15).

The musical piece emerged as expressive sensibilities, building a soundscape that reflected characteristics of the initial experience. This included aspects of stitching (an underlying repetitive rhythm), distorted voice (technological challenges of remote participation and feelings of disconnect), and weaving in of ‘ukulele sounds to provide an aesthetic of hope and reaching (Kinnunen 2024). I reflected on those choices, building short narratives from the experience of composing the work and how it felt to express these feelings with sound. As a continued iterative interrogation of the experience, I was drawn back into language and metaphor and crafted a poetic piece (Kinnunen 2024). The process of crafting the poem allowed me to consider all I had worked through in the various modalities and offered an expression that was not as limiting as prose, serving to round out a cycle and inviting a next potential iteration or layer the following year. Autoethnography as process provides insights into our emotional, embodied and relational experiences in a way that is quite exposing and vulnerable (Holman Jones and Adams 2023) and the use of poetry allowed a way to explore the ineffable and perhaps open up further potential meanings.

The process of taking part in a reflexive loop (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2009) by using multiple artistic modalities of expression and provocation in a sequenced format has helped to continually push my understandings and allow potential for ‘…(re)descriptions, (re)interpretations, or (re) problematisations that add some quality to the text and the results it communicates’ (314) and offer ‘interpretations at deeper levels and reflection’ (315). I have appreciated this process of interweaving creative modalities while contemplating the interactive and interdependent nature of multiple identities and contexts as a kind of systems thinking influenced by the work of Nora Bateson (2023). Bateson challenges us to consider the active, inter-relational nature of all things and the potential of these coalescences. This exploration often resulted in an indulgence in thinking with metaphor, as well. This use of metaphor in reflexive work can be useful, noted by Alvesson and Sköldberg (2009) as providing opportunities for accessing different ways of considering the research and that metaphors should be ‘chosen so as to stimulate reflection and movement between the levels of interpretation’ (312).

The project was guided by research questions that felt more like wonderings I carried with me through the process.

How does it feel to be a middle-aged student in higher education?

How does it feel to be a remote student?

How is my identity or sense of self experienced and affected in this situation?

How does this relate to my own work as a learner, teacher, emerging researcher and artist?

Data Analysis

The initial data included the full text of a daily journal (26,144 words), a set of keywords I composed alongside each daily journal entry (347), and the crocheted blanket. Using Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis approach (2021), I first immersed myself in the dataset with a thorough reading of the full document. I coded the journal texts using both in vivo and descriptive coding, using a combination of a ‘lumper-splitter’ approach for both a holistic view of the texts as well as more minor code fragment analysis (Saldaña 2021: 33-35) which identified some of the potentially meaningful or interesting semantic (explicit) and latent (implicit) meanings and concepts (Braun and Clarke 2021). I coded daily keywords from the journal and reviewed meta notes I had made during the project year, and I made notes and observations as I considered the blanket itself through visual and tactile observation, as well as considering the process of constructing it. Finally, in this initial analysis, I looked at the data holistically to explore patterns and develop categories and themes, taking a few passes over them to reflect and reconsider each time to develop themes. Following the additional creative modalities of music composition and poetry, I gathered words and phrases describing those processes and, using thematic analysis again, brought them into the larger analysis for a zoomed-out view of all of the data. This allowed for a refining, defining and naming of themes that allowed them to be synthesized, storied and presented (Braun and Clarke 2021; Kara 2020).

Discussion

Several overarching themes emerged through this process: vulnerability and uncertainty, belonging and (dis)connectedness, transitions and identity, optimism and reflexive practice, and ritual and reflection. There was a balance and imbalance, an ebb and flow, a push and pull across the themes. I highlight some of the initial results here, noting that my understanding is still emerging and expanding, particularly as I continue to employ this arts-based reflexive practice through my doctoral journey. Each of the groupings begins with a quote taken from my original journal notes.

Vulnerability and uncertainty

‘I struggled with figuring out how to weave the yarns together […] it is difficult and awkward. Clunky and chunky, and my hands don’t work smoothly with it […] It took me a few weeks to get the hang of it, but I’m glad I was persistent.’

Creating something new, in this case using crochet, evoked feelings of awkwardness and the uncomfortable space of being a beginner at something as an adult. It allowed me to reflect on what it meant to be a student again later in life and how navigating that beginner-ness online felt. After spending decades in various roles in work environments, including in leadership, and suddenly finding myself as a novice again was sometimes disconcerting and disempowering. As a first-generation scholar, even at this older age and having previously completed undergraduate and master’s degrees, I noted that feelings of uncertainty and inadequacy were still evident related to the academy’s sometimes nuanced expectations, specialized language, and formal and informal systems and hierarchies. In online spaces, in particular, one experiences a loss of body language cues and other spatial aspects and nuances where potentially different protocols for social behaviour and language barriers may present challenges in communication. This can all have an impact on the development of self-efficacy in student researchers, particularly when those more casual interactions, informal peer partnerships, mentoring and overall culture of the program – all noted as just as crucial to doctoral training (Niehaus et al. 2018) – are not as easy to facilitate online.

This process also revealed how anxiety could rear up at various times, sometimes inhibiting the ability to speak up or interact. As a middle-aged woman, symptoms of the menopausal transition, such as physical and emotional anxiousness, as well as brain fogginess and fatigue, can be part of our daily lives (Bos et al. 2020; Christodoulou 2010; Mosconi 2024). These unexpected challenges occasionally affected confidence and engagement, as well.

Throughout this journey, as I considered the experiences of vulnerability and uncertainty, I deeply resonated with the experiences of the adult participants in the music-making spaces where I teach and facilitate.

Belonging and (dis)connectedness

‘grasping words without expression, without response, flat and linear […] reaching […] staring, glaring, being watched but not seen […] how can communication and community happen here?’

Questions of belonging emerged throughout the experience. In this transitional time and transitional year, moving across multiple roles and identities, where was my tribe? How did I fit into any specific community of practice (Wenger 1998) where I might find commonalities and understandings that allowed me to connect in these spaces together? A sense of outsider-ness coupled with fear of missing out (FOMO) fluctuated throughout the year as a remote student in these hybrid settings. The doctoral program had well-established and successful collaborative learning methods that worked very well in person. Still, as a remote student, I sometimes struggled to experience the same level of collaboration and connection. Indeed, becoming an academic is a ‘social journey in as much as it is an intellectual one’ (Westerlund 2014).

The importance of live, human connection became very clear, particularly opportunities for informal interaction that can strengthen community. For example, at the end of a class when the ‘room’ closed for online participants, sometimes abruptly, casual conversation could continue for those in person. However, this could feel isolating for online students, especially when a lively discussion was had during the class. This is a limitation and reality of technology and distance. At times when a greater number of participants were online during seminars, I noted a greater sense of inclusion. When only one or a few people were online and the majority were in person, it was clear how difficult it could be to engage remote participants, particularly in complex discussions. As leader in that space, it can be very challenging to navigate engagement of online participants as well as their in-person colleagues or participants.

I connected this with my own experiences of teaching and leading using the Zoom platform during the pandemic, as well as in hybrid settings post-pandemic. I considered the difficult role of facilitator in any group environment and all that is attempted to encourage connectedness and belonging (Kinnunen forthcoming 2025). This is a lot for leaders and educators to hold alongside facilitation or pedagogical expectations, to be aware of all these things in hybrid, synchronous spaces. It can be improved by having co-facilitation when possible to enable shared attentiveness to all participants. As noted in Creech et al. (2020: 129), responsive leadership in learning and teaching is invaluable, and I suggest this is the case across all of the contexts I am navigating.

Transitions and identities

‘There is a sort of dance of knowledge, a weaving and unravelling of what I understand and do not […] moving from clarity to blurred focus and then a reconstructing and reattaching, re-stitching of thinking, of purpose, of self.’

At the end of those first nine months, I experienced a sense of accomplishment along with an evolving journey of self, particularly noting the positive changes that had emerged with the reflexive practice. Research and contemplative or critical thinking is also creative work, and they interact, interweave and interleave, one thing informing the other as ongoing transitions through learning and experiencing. We ‘make’ research (Kara, 2020). Along this journey, I noted that those smaller milestones and emergences were critical in helping me recognize my own humanness and growth, and learn to live in the messy middle of those ongoing transitions. A personal shift I made note of was that as I was entering a new chapter in life, I was losing some connections with friends or family. However, I found I was also emerging with a new set of connections. My social and academic networks were evolving and changing, too.

I observed that my language or terminology could impact connections and resonances. Terms like community music, for example, did not necessarily carry the same meaning in this new academic space as the way I had come to understand and use it in my research work or educational environment (Higgins and Willingham 2017). I found myself meandering through interpretations and perspectives within this new context, asking, ‘how do we navigate connections with others when we are not using language in the same way, with the same meanings,’ or rather, ‘how can we navigate this in academic discourse along and between boundaries of disciplines to better understand and explore?’ I learned to trust in the process as an ongoing journey, to be aware of and lean into understanding alternate perspectives and realities, not to be afraid to change my mind or course-correct.

When discussing this project itself, though mostly welcomed as creative exploration, I noted some responses from both inside and outside the academy when I would mention using crochet as a component of the research process. It was occasionally jokingly referred to as being an elderly woman’s activity, or a craft – as in opposition to art, or simply an odd and unserious choice for a research investigation. In discussions about pursuing doctoral studies in general, I was asked why I would ‘do this to my family’ or ‘what was the point of doing this at my age.’ I found myself disappointed with these comments and reflected regularly on perceptions and expectations of women in their roles in family, community, education, and their lived experiences more generally throughout midlife and beyond (Bateson 1989; Lyle and Mahani 2021). Ultimately, after deeply considering my own reasons for this pursuit of learning and of engaging with research that I felt strongly about and was linked so intimately to my practice, I noticed that these kinds of comments often ended up strengthening my sense of self and my resolve to pursue this work, particularly with women.

midlife makes moves we could never expect

and so we still hold tight to threads and tones and tendrils

the possibility of one moment and all moments

in us and wherever we may end

excerpt from the poem unravelling the edge of me (Kinnunen 2024)

Optimism and reflexive practice

‘Support for each other’s work, challenge and questioning, and some humour and humanness. It was exactly as I hope that interactions around our research work can be. This was reassuring, with a wealth of feedback from a range of points of view… noting where I might improve and clarify, where I was clear and provocative in strong ways. It reignited my excitement. I felt seen in a respectful and engaged space.’

There was a great deal of optimism and stimulating learning throughout the process. It was meaningful for me to look back and notice words likepotential, possibility, purpose, excitement and gratitude, phrases like collegial discussion, democratic space and respectful conversations. There wereunfoldings and discoverings. In particular, these often correlated to times when all participants were engaged in these spaces and when I, as a remote student, felt seen and welcomed with lively, provocative and inclusive discussions, and when I felt I could contribute even with my different perspectives or emerging knowledge. I would make a connection with the foundational CM principles I carry with me in my own teaching and facilitation practice (Higgins and Willingham 2017).

Reflexive practice throughout this journey was an intimate, eye-opening and ultimately rewarding experience that not only allowed me to consider my personal experiences about who I am or am always becoming but also deepened my understanding of the importance of reflexive work in my practice and my emerging research. This locating of self within the research (Kara 2020: 95) recognizes I am not ‘a neutral presence’ in this work and that autoethnographic work is ‘perhaps the most fully reflexive type of research’ (Leavy cited in Kara 2020: 95). Beginning to understand and take ownership of the researcher’s presence within the exploration as valuable was both eye-opening and validating.

Ritual and Reflection

‘Sometimes the colour I need to reattach is the colour I’ve severed the previous week.’

Looking back at the data and the project itself, I realized the importance of this ritual or habit of daily and weekly practice. The process of Saturday morning crochet offered a few hours each week carved out for me to review and reflect on the week’s journaling, to assign colours for each day, and to stitch seven new rows onto the blanket. It became a meaningful time of care and contemplation and was an important way to be present with myself and gently open things up. The tactile process of this crochet work prompted regular metaphorical connecting to the stitching, reflecting the ease or frustration I felt about these various contexts (Riley, Corkhill and Morris 2013; Sjöberg and Porko-Hudd 2019).

For example:

The struggle of trying to weave in ends or join one thing into another as seamlessly as possible provoked thinking around imperfection, around the tensions of linking or transitioning between contexts and roles on a regular basis, of recognizing the overlap of beginnings and endings in liminal spaces.

If my hands were aching after a time, it sometimes meant I was over-gripping the hook, so I would ask myself how I might be mindful of holding or loosening control in my various roles and identities.

The heaviness of the blanket, of carrying a project over time and turning it over for each new row of stitches, prompted thinking around the weight of making, of creating, of holding and of contemplative work, all aspects of teaching and facilitation that require reflection and self-awareness.

This experience also highlighted the importance of ritual or routine for participants in my teaching and facilitation spaces and a reminder for myself to build in regular self-care and reflection. It drew me, for example, towards thinking about the format and expectations in the doctoral seminars and how once those were understood, offered some reassurance knowing how things would proceed, what expectations were and how we moved through that time together. I recognize this anticipated structure helps to open up space for other deeper or more provocative experiences, creativity, and flexibility to emerge in both higher education spaces as a learner and in my CM practice.

Continuing the work

‘I believe in the need for multiple models so that it is possible to weave something new from many different threads’ (Bateson 1989: 16).

Our identities are changing and evolving throughout our lives, being constructed and challenged based on our interactions with others (Hallam et al. 2017; Lowery 2023). Considering musical spaces, Creech et al.’s (2020) ideas of possible selves demonstrate that the ways we encounter musical learning and practice throughout our lives shape our self-stories of musical possible selves. ‘[…] the individual and the collective are routinely entangled with each other’, and identification comes within interaction (Jenkins 2014: 140). I recognized the many ways I was learning throughout this process: as a returning student, as a middle-aged woman, as a facilitator or teacher, as an emerging scholar, as a musician or creator, and all of these encounters and roles interweaving did indeed (and continue to) shape how I see myself in music and musicking in all of its various iterations and identities. I also recognized the importance of noting how I am reconciling my imagined identity with that of the current reality or context I am in, whether as a student, a researcher or a practitioner, and the impact that tension can have in those contexts.

Similar to Turner’s (2017) process and experience through her doctoral autoethnographic work using arts-based practice, I began to notice the reflexive aspects of this multi-modal approach opened me up to considering the blurred lines, benefits and tensions of the interleaving nature of the multiple roles we play as artists-researchers-practitioners. She points to Billot (2010: 710), noting ‘How an academic contextualizes their identity has an impact on the way [that] they make sense of their workplace […] the changing context for academics is laden with tension as the academic seeks to understand or reconcile their imagined identity (associated with the past, present and future constructions) with that of their current reality.’ Turner (2017) suggested she could replace the word ‘academic’ with ‘community musician’ or ‘artist’; I would also add ‘student’ and ‘woman in midlife’.

I hope to continually remind myself of the value of reflecting on and giving weight to all of the colours, emotions, and interweaving lived experiences I have across my various roles and identities, particularly as a researcher, an educator, and a community music practitioner. I make a note of the similar ‘inside-outside-upside-downside’ experience of positionality and multiple roles moving between research and practice shared in Evison (2022). Making time for reflexive arts practice as facilitators or educators can help us make sense of our topsy-turvy experiences. It can help us recognize our own humanness and the impacts these roles and experiences have on us as practitioners.

I will maintain the project throughout my Ph.D. as it offers benefits ranging from practical self-care and personal creativity to meaningful reflexive potential related to research and practice. I have recently completed the second blanket and am analysing, creating, and reconsidering through various modalities. It has become an important reflexive and iterative practice, and the journaling component has become broader in documenting experiences, encompassing more of the various aspects of this journey and the Ph.D. research itself. I was reminded of a comment I heard at a recent conference on autoethnography and narrative inquiry, touching on the potential for narrative entrapment and that in our research, whether we are working with ourselves or others, we must note that when something is written down, it can become a way of ‘locking us down’ in that narrative. It is important that we recognize that ‘this is where I am now’ and ‘next week something else might happen’ to keep the pieces fluid and transitioning, just as our human experience. Ongoing exploration through creative processes can help to address this fluidity and iterative process, these many ways of knowing and knowing ourselves. I am being worked on as much as I’m doing the work (Romanyshyn 2021).

REFERENCES

Adams, T. E. & Herrmann, A. (2023). ‘Good Autoethnography’. Editorial in Journal of Autoethnography, 4(1), pp. 1-9.

Alvesson, M. & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research (2nd ed.), London: Sage Publications.

Bateson, M.C. (1989). Composing a Life, New York: Grove Press.

Bateson, N. (2023). Combining, Axminster: Triarchy Press.

Bochner, A. & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative Autoethnography: Writing Lives and Telling Stories, New York: Routledge.

Bos, N., Bozeman, J. H., Frazier-Neely, C. (2020). Singing Through Change: Women’s Voices in Midlife, Menopause, and Beyond, Suquamish: StudioBos.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, London: SAGE Publications.

Bridges, W. & Bridges, S. (2019). Transitions: Making Sense of Life’s Changes, New York: Hachette.

Christodoulou, J. A. (2010). Identity, Health and Women. A Critical Social Psychological Perspective, Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Creech, A., Varvarigou, M., Hallam, S. (2020). Contexts for Music Learning and Participation: Developing and Sustaining Musical Possible Selves, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

Creswell, J.W. & Poth, C.N. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Danylova, T., Ilchuk, S., Storozhuk, S., Poperechna, G., Hoian, I., Kryvda, N., & Matviienko, I. (2024). ‘Best before: On women, ageism, and mental health’. In Mental Health: Global Challenges, 7(1), pp.81-94.

Dwyer, S. C. & Buckle, J. L. (2009). ‘The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research’. In International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), pp. 54-63.

Etherington, K. (2004). Becoming a Reflexive Researcher: Using our Selves in Research, London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Evison, F. (2022). ‘Inside, outside, upside, downside: Navigating positionality as a composer in community music’. In Transform: New Voices in Community Music.

Feiler, B. (2020). Life is in the Transitions: Mastering Change at Any Age, New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

Goethe, J. W. ([1840]1970). Theory of Colours, translated from the German by Charles Lock Eastlake, London: M.I.T. Press.

Hallam, S., Creech, A., Varvarigou, M. (2017). ‘Well-being and music leisure activities through the lifespan: A psychological perspective’. In The Oxford Handbook of Music Making and Leisure, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 31-50.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013). Why Music Matters, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Higgins, L. & Willingham, L. (2017), Engaging in Community Music: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Holman Jones, S. & Adams, T. (2023). ‘Autoethnography as becoming-with’. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, pp. 421-436.

Holmes, A. G. D. (2020). ‘Researcher positionality: A consideration of its influence and place in qualitative research, A new researcher guide’. In Shanlax International Journal of Education, 8(4), pp. 1-10.

Irwin, R.L., Pardiñas, M.J.A., Barney, D.T., Chen, J.C.H., Dias, B., Golparian, S., MacDonald, A., Irwin, R.L., MacDonald, A., Barney, D, R. L. (2017). ‘A/r/tography around the world’. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Arts Education, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 475-496.

Irwin, R.L., LeBlanc, N., Ryu, J. Y., Belliveau, G. (2018). ‘A/r/tography as living inquiry’. In Handbook of Arts-based Research, Guilford Publications.

Jenkins, R. (2014). Social Identity. (4th ed.), London: Routledge.

Kara, H. (2020). Creative Research Methods: A Practical Guide, Bristol: Policy Press.

Kinnunen, C. (2024). ‘Unravelling the edge of me’. In Unpsychology. 10(1). Raw Mixture Publishing. https://unpsychology.substack.com/p/unravelling-the-edge-of-me

Kinnunen, C. (forthcoming 2025). ‘Can ‘ukulele keep us together? Exploring experiences of courage and connection in adult learning groups in online settings during the pandemic’. In J Lang (Ed.) Music and Wellbeing in Education and Community Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars.

Lachman, M. E., Teshale, S., Agrigoroaei, S. (2015). ‘Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age’. In International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), pp. 20-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414533223

Leavy, P., (Ed.). (2018). Handbook of Arts-based Research, Guilford Publications.

Lowery, B. (2023). Selfless: The Social Creation of “You”, HarperCollins Publishers.

Lyle, E., Mahani, S. (Eds.). (2021). Sister Scholars: Untangling Issues of Identity as Women in Academe, New York: DIO Press Inc.

Mosconi, L. (2024). The Menopause Brain, New York: Avery/Penguin Random House.

Niehaus, E., Garcia, C., Reading, J. (2018). ‘The road to researcher: The development of research self-efficacy in higher education scholars’. In Journal for the Study of Postsecondary and Tertiary Education, 3, pp.1–20.

Popova, M. (n.d.) Goethe on the Psychology of Color and Emotion. The Marginalian. Retrieved September 30, 2024. https://www.themarginalian.org/2012/08/17/goethe-theory-of-colours/

Riley, J., Corkhill, B., Morris, C. (2013). ‘The benefits of knitting for personal and social wellbeing in adulthood: Findings from an international survey’. InBritish Journal of Occupational Therapy, 76(2), pp. 50-57.

Romanyshyn, R. D. (2021). The Wounded Researcher: Research with Soul in Mind, Oxon: Routledge.

Saldaña, J. (2021). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, London: SAGE.

Sjöberg, B. & Porko-Hudd, M. (2019). ‘A life tangled in yarns: Leisure knitting for well-being’. In Techne serien-Forskning i slöjdpedagogik och slöjdvetenskap, 26(2), pp. 49-66.

Springgay, S., Irwin, R. L., Kind, S. W. (2005). ‘A/r/tography as living inquiry through art and text’. In Qualitative Inquiry, 11(6), pp. 897-912.

Thomas, A.J., Mitchell, E.S., Pike, K.C.,Woods, N.F. (2023). ‘Stressful life events during the perimenopause: longitudinal observations from the seattle midlife women’s health study’. In Women’s Midlife Health, 9(1), p.6.

Turner, K. (2017). ‘“The lines between us”: Exploring the identity of the community musician through an arts practice research approach’. In Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy 17(3), Grieg Academy Music Therapy Research Centre.

Veblen, K. (2007). ‘The many ways of community music’. In International Journal of Community Music, 1(1), pp. 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.1.1.5_1

Wenger, E. (1998). ‘Communities of practice: learning as a social system’. In Systems thinker, 9(5), pp. 2-3.

Westerlund, H. (2014). ‘Learning on the job: Designing teaching-led research and research-led teaching in a music education doctoral program’. In Research and Research Education in Music Performance and Pedagogy, pp.91-103.