Troulou, R. (2024) – Download PDF – pp. 88-102

Department of Music, Science and Art

University of Macedonia

rafaelatroulou@uom.edu.gr

Abstract

I begin with the first question of the research instrument: “Are you satisfied with your life?” She is asked to answer yes or no. Instead of giving me one of the two expected answers, she begins to narrate and cry while holding my hand. As a researcher, I have to set a boundary. As a human being, I can’t. I try to continue with the second question. She gets emotional again. Then, as a community musician, I think: instead of asking her the next question, I’ll ask this one: What is your favourite song? I start singing and she follows me […]. We didn’t manage to complete the questionnaire…The impetus for this paper comes from my experience as an early-stage researcher and practitioner conducting a community music intervention with institutionalized older adults in Greece. Through the process of exploring my threefold nature in this context – as a researcher, as a practitioner, and as a human being – the following issues are addressed: (1) the emerging dilemmas in relation to ethics, (2) the dimensions of ethical dilemmas and the complex web in which they are entangled, (3) the notion of ‘reflexivity’ as a promising response to these dilemmas.

Keywords: Community music research; community music practice; ethics; ethical dilemmas; reflexivity.

Introduction – Setting the scene

The impetus for this paper came from my experience as a PhD researcher and community musician. My PhD aimed to investigate the impact of a community music intervention on the psychological and emotional wellbeing of older people. In this context, a community music programme was implemented in two nursing homes in Greece, from July 2022 to May 2023, with 43 older people participating.

The characteristics of the people involved in the music sessions were diverse in terms of their cognitive and psychological states, functional abilities, as well as socioeconomic and family status. Despite their heterogeneity in these aspects, this population shared a common experience; they were all facing the negative consequences that accompany the experience of residing in an institutional setting.According to the relevant literature (Choi et al. 2008; Kane 2001; Tuckett 2007), relocation and residence in nursing homes negatively impact the wellbeing and quality of life of older people, usually affecting their sense of motivation and purpose in life, as well as their general mood and sense of independence. All these health- and psychosocial-related conditions put the population involved in the research study and community music intervention in the position of being considered ‘vulnerable’ (Sanchini et al. 2022).

The research employed a mixed-methods methodology and a pre-test–post-test design to measure the programme’s/intervention’s effect on participants’ wellbeing levels. The rationale behind applying a mixed-methods approach and using both quantitative and qualitative means of collecting data was for triangulation (Patton 1990). I had the role of the researcher in the process of collecting, analysing, and synthesising data and I was also the facilitator of the community music intervention. Before and after the implementation of the community programme, I administered two quantitative researchquestionnaires: the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). The selection of these specific questionnaires was driven by the lack of more suitable research instruments translated into Greek and validated for the Greek population, and the fact that their administration does not require prior specific training. Furthermore, both instruments find frequent use in studies related to the music, wellbeing, and old age agenda.

The MMSE (Folstein et al. 1975; Fountoulakis et al. 2000) is a well-known tool for the cognitive assessment of older people, while the GDS (Fountoulakis et al. 1999; Yesavage et al. 1982) measures levels of depression and overall subjective wellbeing in older populations. Besides quantitative measures, qualitative methods were employed. All music sessions were video-recorded and transcribed into a researcher’s diary, and semi-structured interviews were conducted with care staff members. The purpose of employing these qualitative methods was to illustrate the program’s effect on participants’ wellbeing. However, this paper focuses on the quantitative research procedures, specifically those conducted during the pre-test period (i.e., the period when quantitative tests were administered prior to implementing the community music programme/intervention).

The community music intervention included singing and rhythmic playing on small percussion instruments to accompany songs. Music-making on the spot as well as improvisation were also encouraged. Older people were invited to get involved in the musical activities in whatever way they felt most comfortable, and their involvement could range from simple observation (e.g. listening) to full participation (e.g. singing, moving in rhythm, playing percussion instruments), depending on their desire and mood. Great emphasis was placed on creating a safe and inclusive environment through collaborative music-making, fostering core principles of community music practice, such as friendship, sense of agency, and belonging (Higgins 2007; Higgins 2012; Van der Merwe et al. 2021).

Through exploring the ethical dilemmas that arise from my threefold nature in this project as a researcher, community musician, and human being, I will discuss how these roles often intersect and conflict and how the tensions, boundaries, concerns, and connections are evolving. By building a theory supported by existing literature and based on my experience as an early-stage researcher and practitioner in community music, I will indicate how a more reflexive approach in research and practice can provide a more ethical response towards our study, participants, and ourselves.

My threefold nature and the concept of ethical dilemmas

Given that vulnerable individuals were involved in the research study, ethical approval and written consent from the participants or their ‘significant others’ were required. Once ethical approval was granted by the Committee for Research Ethics of the University of Macedonia and the written consent forms were obtained, I visited the two nursing homes to administer the two research questionnaires. Although I was very well prepared – from the researcher’s perspective – to conduct the tests effectively, I was not prepared for the unexpected aspects of this process; the participants’ unexpected answers and reactions, which led to a series of interrelated ethical dilemmas.

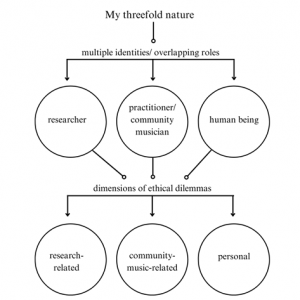

Using the term ‘ethical dilemmas’, I refer to the ethical concerns and tensions related to my threefold nature in this research project. This project involves practices in which I am supposed to manage multiple identities and overlapping roles: (1) as a researcher (i.e., selecting the appropriate research strategy/ methodology, administering research questionnaires, collecting and analysing data, etc.), (2) as a community musician (i.e., setting up the community music intervention, facilitating music sessions), and (3) as a human being (i.e., the values, morals, and beliefs I have as a person). These identities and roles constitute my threefold nature, and, in turn, shape a three-part model of dimensions related to ethical dilemmas: (1) research-related ethical dilemmas (dilemmas associated with research ethics), (2) community-music-related ethical dilemmas (dilemmas related to the ethics of community music and the basic principles of community music-making), and (3) personal ethical dilemmas (dilemmas associated with my ‘ethos’; my character of being, personality, and personal morals). The following figure summarises the complex web of my threefold nature, representing my multifaceted role in this project and the interrelated dimensions of ethical dilemmas.

Figure 1. The complex web of my threefold nature.

As indicated in the literature (Guillemin & Gillam 2004; Reid et al. 2018), research-related ethical dilemmas include ‘procedural ethics’, i.e., ethics associated with the process of obtaining approval to conduct research from a specialised ethics committee, and ‘process ethics’, i.e., in-the-moment ethics that occur throughout the research practice. Such dilemmas occur when human interaction is involved in the research process and often emerge after a significant disclosure or statement is made by the respondent or discomfort is implied in a response (Guillemin & Gillam 2004). These ethical concerns and tensions arise unexpectedly and require the researcher to decide whether to respond to the statement or let it go, what to answer and in what tone, and whether to stop or continue the process of conducting an interview/administering a research questionnaire (Guillemin & Gillam 2004).

The second dimension of ethical dilemmas, the community-music-related ones, are linked to the principles of community music-making as well as the values and virtues associated with participatory music-making (Lines 2018). The principles of community music are related to people, place, participation, inclusion, and diversity (Higgins & Willingham 2017) and some values and virtues associated with community music practice include – but are not limited to – the notions of hospitality, welcoming, excellence, sense of agency, love, friendship, care, compassion, democracy, social justice, peace-making, and activism (Bartleet & Higgins 2018; Henley & Higgins 2020; Higgins 2007, 2012; Howell et al. 2017; Morelli 2022; Silverman 2012). The concept of relationality and the relationships formed between community musicians and participants are considered crucial in supporting the ethics of community music practice, because as community musicians ‘we are called to live, sing, dance and create in the space between conditioned and unconditioned and to celebrate the potentialities of relationality in this space’ (Morelli 2021:278).

The third dimension, personal ethical dilemmas, is considered of great significance, because ‘we cannot have ethics without ethos’ (Gouzouasis 2019: 241). The word ‘ethos’ has a dual meaning in the Greek language (Gouzouasis et al. 2014), but in this context, it is used to denote the ‘distinguishing character, sentiment, moral nature, or guiding beliefs of a person’ (Merriam-Webster dictionary n.d.), derived from the ancient Greek word ἦθος [pronounced eethos] (Gouzouasis 2019).

My multiple identities and overlapping roles – and the ethical dilemmas that accompany them– were either interrelated or in conflict. There were times when I had to decide whether to be satisfied with myself as a ‘conventional’ researcher, as a human being, or as a community musician. There were also times when my skills as a community musician were inevitably involved in research processes. In other words, there were times when in-the-moment research ethical concerns emerged, requiring me to choose whether to respond with the role of the researcher, the role of the community musician, or according to my morals and values. Simultaneously, I was concerned, on the one hand, with preserving the integrity of the research process, and on the other hand, being sensitive to participants, always mindful of their vulnerability. The following extracts, derived from the process of administering the two research questionnaires, depict the complex web of the overlapping ethical dilemmas I confronted, and illustrate the tensions arising in the framework of my threefold nature:

Τhe process of administering the test is going as it should. It is that part of the test (i.e., Mini Mental State Examination) where they are asked to write down a sentence of their choice. She takes the pencil and writes: ‘I miss my children’. She hands me the paper as tears stream down her face. I wonder if I should move past her emotional reaction and move on to the next task on the test, as I should… but I can’t… I know that as a researcher I have to put a boundary between us; I have to continue the administration process. But my ethics as a human being and the way I think and act as a community musician cannot allow me to just let this pass…I can’t just end the questionnaire and leave her with this feeling. At least I should try by doing what I know best [..] I grab my ukulele and suggest that we sing a song of her choice together…

I begin with the first question of the research instrument (i.e., Geriatric Depression Scale): ‘Are you satisfied with your life?’ She is asked to answer yes or no. Instead of giving me one of the two expected answers, she begins to narrate and cry while holding my hand. As a researcher, I have to set a boundary. As a human being, I can’t do that. I try to continue with the second question while still holding her hand. She gets emotional again. Then, as a music facilitator, I think: Instead of asking her the next question, I’ll ask this one: What is your favourite song? I start singing and she follows me […]. We didn’t manage to complete the questionnaire…

Reflexivity and connected ethical dilemmas

Examples such as those mentioned, where the researcher encounters unexpected and often uncomfortable situations, are common when qualitative research strategies are implemented (Guillemin & Gillam 2004; Othman & Hamid 2018), either independently or in conjunction with quantitative methods, as in this case where a mixed-methods approach was followed. Unexpected challenges can also arise when the topic under investigation is sensitive (Othman & Hamid 2018) or when the individuals involved require a more sensitive approach due to their vulnerability, such as in this specific research project.

These unexpected moments and situations can be laden with even more tension in situations where the researcher is also the practitioner, as in this case. As emphasised in the relevant qualitative research literature (Arber 2006; Guillemin & Gillam 2004; Reid et al. 2018), a significant degree of ‘reflexivity’ is required if the researcher is also to share the identity of the practitioner and wants to adopt an ethical research practice, ensuring an ethical response to participants. Reflexivity can act as a means of bridging the tensions and boundaries between research and practice (Etherington 2004) and recognises that the intersubjective dynamics between researcher and participants have a significant impact on the research process (Finlay 2003; Finlay & Gough 2003). Reflexivity accepts that subjectivity and engagement during the research process do not necessarily lead to research bias (Finlay & Gough 2003) and acknowledges that both sides (researcher and participants) have agency in the research process (Etherington 2004), recognising that research is ‘a joint product of the participants, researcher, and their relationship’ (Finlay 2003:5).

As indicated in the examples quoted, the statements and emotional discomfort of the participants, triggered by certain items in the questionnaires, placed me in a position where I had to decide whether to continue or stop the administrative process and how to respond to their statements. How I dealt with these research-related ethical dilemmas is connected to the second dimension of overall ethicaldilemmas; the community-music-related ones. My actions as a community musician were essential in resolving tensions that arose due to completing the questionnaires. As my actions as a community musician helped in resolving tensions, acting as a community musician was crucial. Additionally, as a researcher and practitioner in this project, I have found that community-music-related ethical dilemmas are connected to research-related ones.

Although, at first glance, it may appear that community-music-related ethical dilemmas occur only during community music practices, given that I hold both the role of researcher and practitioner in this research project, it could be that community-music-related ethical dilemmas are intertwined with research-related ones throughout the entire process. The connection between the community-music-related ethical dilemmas and the research-related ones inspired the following reflective questions:

How can I/we as (a) practitioner(s) facilitate the principles of community music-making if I/we as (a) researcher(s) neglect them?

How can I/we as (a) practitioner(s) foster and encourage the ethics of community music practice if my/our enactment as (a) researcher(s) doesn’t support them from the very beginning?

How can I/we cultivate a safe and inclusive space in community music sessions if I/we have triggered insecurity and discomfort in the first place?

These questions emerged because of my training in community music practice and devotion to the community music principles. Furthermore, these questions suggest that our actions as researchers influence our actions as community musicians, and vice versa. Considering, also, that in community music practice the dynamics between facilitator and participants are crucial to the way the process of music-making unfolds, and that participants and facilitator are involved in a complex web of relationships and interactions (Higgins 2009, 2012; Morelli 2021), some important connections with the theme of reflexivity can be recognised. This thesis is also supported by Turner (2020) who points to the need to integrate reflexive practice into our work as community musicians by asking critical questions and adopting an ethical stance as facilitators, researchers, and musicians.

Furthermore, it has been addressed that reflexivity is part of our essential human capacity (Finlay & Gough 2003), a fact that links the issue of reflexivity to the third dimension of ethical dilemmas; the personal ones. As evidenced in the questionnaire administration excerpts, my moral codes and the way I think and act as a human being brought me into situations where my role as a researcher and my identity as a human being came into conflict. At this point, it is important to emphasise that receiving ethical approval from a research committee does not guarantee ethical behaviour towards participants; it only guarantees that the research methodology and strategy intend to adhere to the rules of research ethics at every stage of the research. In other words, ethical approval doesn’t guarantee an ethical research practice and behaviour, since the researcher is not inspected by the committee at any stage of the research (Guillemin & Gillam 2004). This fact supports the idea that personal morals and values – i.e., personal ethics – play a significant role in conducting ethical research, and are thus linked to research-related ethics.

Additionally, our attributes as human beings, including our personality traits, and our personal beliefs and values, are strongly connected to our enactment as community musicians (Howell et al. 2017), indicating a strong tie between personal ethics and community-music-related ethics. Building upon the ideas presented in the references (i.e. Higgins, 2009; Higgins 2012; Howell et al. 2017; Lines, 2018), it is my understanding that being a community musician is a way of being; a way of enactment in all aspects of life, not just a way of enactment when facilitating music sessions. In my view, our traits and morals influence our practice as community musicians, and conversely, our practice and training in community music significantly impact our way of understanding people, places, inclusion, diversity, friendship, agency, love, care – and other notions linked to the ethics of community music practice – in a way that goes beyond the process of music-making. According to Howell et al. (2017: 606), music facilitators ‘engage with people to find pathways through which music-making opportunities might allow them to personally flourish with full and engaged participation’. I extend this statement by positing that music facilitators not only offer pathways for flourishing to potential participants but also to themselves, as they are also fully engaged in the community music experiences.

Discussion – Concluding Thoughts

My threefold nature has involved me in a series of interrelated ethical dilemmas throughout this research project. There were moments when the boundaries between the different identities and overlapping roles I was supposed to manage were blurred, creating occasions of tension where decisions regarding ethical dilemmas had to be made. Despite these boundaries and moments of tension, combining characteristics from my different identities and roles led me to moments of freedom. In situations where issues of tension and boundaries emerge, reflexivity can offer us – as researchers, practitioners, and human beings – moments of freedom and an opportunity to reflect on our responses to the people involved in our practices and ‘use that knowledge to inform our actions, communications, and understandings…’ (Etherington 2004:19).

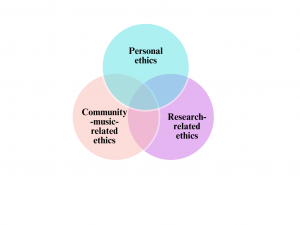

In my experience, and as I have outlined above, the code of ethics when practice and research are combined in the field of community music is complex and can be pictured using a Venn diagram, where personal, research-related, and community-music-related ethics intersect. Therefore, how we, as researchers, respond to ethical dilemmas can impact our work as community musicians, and vice versa; our values as community musicians might influence how we respond to these dilemmas. Our personal ethics are the umbrella under which our research-related ethics and community music-related ethics stand, signalling that personal ethics play a crucial role in this process, as it is ultimately our personal responsibility to affirm the research-related ethics (Guillemin & Gillam 2004) and our commitment to follow the community-music-related ones.

Figure 2. Code of ethics in community music research and practice.

I understand how I conducted the quantitative tests might draw criticism from some quantitative researchers who advocate objectivism in the research process. However, subjectivism is now well recognised in qualitative research and perhaps needs to gain more ground when mixed-methods approaches are used or when vulnerable populations are included in research practice. After all, sensitivity to participants and flexibility during the research process, to maintain a more ethical approach to research and practice, need not necessarily lead to ambiguity in research. Pavlicevic et al. (2013) also emphasise the importance of more reflexive, practice-guided research approaches, arguing that the specific complexities of the population and context in which research is conducted should shape research procedures. Additionally, the literature highlights the need for a more reflexive approach in both research and practice, particularly when working with older populations (Van der Merwe et al. 2021; Wentink & Van der Merwe 2023). Such an approach implies an ethic of care, recognizing that ‘we are relational beings and as such, being allowed to care for the older adults’ (Wentink & Van der Merwe 2023: 15).

At this point, it is worth noting that adopting a more reflexive outlook on the process of data collection and method selection has raised important questions for further investigation. These questions pertain to whether using quantitative research instruments to measure the impact of the intervention was suitable for the study’s setting and the careful ethical frameworks required when working with vulnerable populations. In this study, the use of questionnaires was driven by expectations for quantifiable metrics to measure impact in a standardized way. However, as suggested in this paper, standardized ways of research and practice might not be suitable in community music-making settings involving vulnerable participants.

Thus, reflective, adaptive, and flexible qualitative or mixed-methods approaches might be considered more suitable. In the context of my research, qualitative methods of collecting data were also incorporated, such as semi-structured interviews and observation through video recordings. The preliminary analysis of quantitative and qualitative data shows that qualitative methods allowed for a deeper exploration of the intervention’s impact compared to quantitative ones; a preliminary finding consistent with previous research (e.g. Camic et al. 2011; González-Ojea et al. 2022; Ihara et al. 2018; Yap et al. 2017).

Future ethical planning could include more flexible approaches to data collection and ways to address emergent ethical dilemmas and unexpected emotional responses from participants. Although the ethical approval panel primarily functions to grant initial approval, incorporating iterative reviews could provide an opportunity to adapt the ethical approach as the research progresses, enabling the research plan to evolve. This might involve periodic check-ins with advisors, supervisors, or other relevant professionals.

In conclusion, the present paper highlights the complex interplay between research ethics, community music principles, and personal morals, when research and practice are combined in the field of community music. It also suggests that by adopting a more reflexive approach, as researchers and practitioners, and by acknowledging that ethical research practice extends beyond formal approvals and methodologies we can ensure that our work not only adheres to ethical standards but also respects the quality of life and wellbeing of populations we are engaged. Such an approach implies that our actions as researchers and community musicians are deeply intertwined and require a commitment to personal values and the principles of community music, fostering an environment of inclusivity, respect, and care. With this lens, we can approach the ethical complexities of our work, fostering research that is both ethical and respectful to everyone involved.

Acknowledgments

The author’s doctoral research has been supported by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (H.F.R.I.) through funding awarded under the 3rd Call for PhD Candidates.

References

Arber, Anne (2006), ‘Reflexivity’, Journal of Research in Nursing, 11:2, pp. 147–157.

Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh and Higgins, Lee (2018), ‘Introduction: an Overview of Community Music in the Twenty-First Century’, in B. Bartleet & L. Higgins (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–20.

Camic, Paul M., Williams, Caroline Myferi and Meeten, Frances (2011), ‘Does a ‘Singing Together Group’ Improve the Quality of Life of People with a Dementia and Their Carers? A pilot evaluation study’, Dementia, 12:2, pp. 157–176.

Choi, Namkee, Ransom, Sandy and Wyllie, Richard J. (2008), ‘Depression in Older Nursing Home Residents: the Influence of Nursing Home Environmental Stressors, Coping, and Acceptance of Group and Individual Therapy’, Aging and Mental Health, 12:5, pp. 536–547.

Etherington, Kim (2004), ‘Research methods: Reflexivities‐Roots, Meanings, Dilemmas’, Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 4:2, pp. 46–47.

Finlay, Linda (2003), ‘The Reflexive Journey: Mapping Multiple Routes’, in L. Finlay and B. Gough (eds), Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 3–20.

Finlay, Linda and Gough, Brendan (2003), ‘Introducing Reflexivity’, in L. Finlay and B. Gough (eds), Reflexivity: A Practical Guide for Researchers in Health and Social Sciences, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 1–2.

Folstein, Marshal F., Folstein, Susan E. and McHugh, Paul R. (1975), ‘Mini-Mental State’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12:3, pp. 189–198.

Fountoulakis, Konstantinos N., Tsolaki, Magda, Chantzi, Helen and Kazis, Aristides (2000), ‘Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE): a Validation Study in Greece’, American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 15:6, pp. 342–345.

Fountoulakis, Konstantinos N., Tsolaki, Magda, Iacovides, Apostolos, Yesavage, Jerome, O’Hara, Ruth, Kazis, Aristeidis and Ierodiakonou, Ch. (1999), ‘The Validation of the Short Form of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in Greece’, Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 11:6, pp. 367–372.

González-Ojea, María José, Domínguez-Lloria, Sara and Pino-Juste, Margarita (2022), ‘Can Music Therapy Improve the Quality of Life of Institutionalized Elderly People?’, Healthcare, 10:2, p. 310.

Gouzouasis, Peter, Bakan, Danny, Ryu, Jee Y., Ballam, Helen, Murphy, David, Ihnatovych, Diana, Virág, Zoltan and Yanko, Matthew R. (2014), ‘Where do Teachers and Learners Stand in Music Education Research? A Multi-Voiced Call for a New Ethos of Music Education Research’, International Journal of Education and the Arts, 15:15, n.pag.

Gouzouasis, Peter (2019), ‘A/r/tographic Inquiry in a new Totality: the Rationality of Music and Poetry’, in P. Leavy (ed), Handbook of arts-based research, New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 233–246.

Guillemin, Marilys and Gillam, Lynn (2004), ‘Ethics, Reflexivity, and “Ethically Important moments” in Research’, Qualitative Inquiry, 10:2, pp. 261–280.

Henley, Jennie and Higgins, Lee (2020), ‘Redefining Excellence and Inclusion’, International Journal of Community Music, 13:2, pp. 207–216.

Higgins, Lee (2007), ‘Acts of Hospitality: the Community in Community Music’, Music Education Research, 9:2, pp. 281–292.

________ (2009), ‘Community Music and the Welcome’, International Journal of Community Music, 1:3, pp. 391–400.

________ (2012), ‘One-to-One Encounters: Facilitators, Participants, and Friendship’, Theory Into Practice, 51:3, pp. 159–166.

Higgins, Lee and Willingham, Lee (2017), ‘Introduction’, in L. Higgins and L. Willingham (eds), Engaging in community music: an introduction, New York: Routledge, pp. 1–8.

Howell, Gillian, Higgins, Lee and Bartleet, Brydie-Leigh (2017), ‘Community Music Practice’, in R. Mantie & G. D. Smith (eds), The Oxford Handbook of music making and leisure, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 601–618.

Ihara, Emily S., Tompkins, Catherine J., Inoue, Megumi and Sonneman, Sonya (2018), ‘Results from a Person‐Centered Music Intervention for Individuals Living with Dementia’, Geriatrics and Gerontology International, 19:1, pp. 30–34.

Kane, Rosalie A. (2001), ‘Long-Term Care and a Good Quality of Life’, The Gerontologist, 41:3, pp. 293–304.

Lines, David (2018), ‘The Ethics of Community Music’, in B. Bartleet and L. Higgins (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 385–402.

Merriam-Webster dictionary (n.d.), ‘Ethos’, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethos. [Accessed 3 June 2024].

Morelli, Janelise (2021), ‘Relationality as Ethical Foundation for Community Music Practice’, in J. Boyce-Tillman, L. Van der Merwe and J. Morelli (eds), Ritualised belonging: Musicing and Spirituality in the South African Context, Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 269–82.

________ (2022), ‘(Un)caring: A Framework for Understanding Care in Community Music(k)ing’, International Journal of Community Music, 15:3, pp. 323–340.

Othman, Zaleha and Hamid, Fathilatul Z.A. (2018), ‘Dealing with Un(Expected) Ethical Dilemma: Experience from the Field’, The Qualitative Report, 23:4, pp. 733-741.

Patton, Michael Quinn (1990), Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed.), London: Sage Publications.

Pavlicevic, Mercédès, Tsiris, Giorgos, Wood, Stuart, Powell, Harriet, Graham, Janet, Sanderson, Richard, Millman, Rachel and Gibson, Jane (2013), ‘The “Ripple Effect”: towards Researching Improvisational Music Therapy in Dementia Care Homes’, Dementia, 14:5, pp. 659–679.

Reid, Anne-Marie, Brown, Jeremy M., Smith, Julie M., Cope, Alexandra C. and Jamieson, Susan (2018), ‘Ethical Dilemmas and Reflexivity in Qualitative Research’, Perspectives on Medical Education, 7:2, pp. 69–75.

Sanchini, Virginia, Sala, Roberta and Gastmans, Chris (2022), ‘The Concept of Vulnerability in Aged Care: a Systematic Review of Argument-Based Ethics Literature΄, BMC Medical Ethics, 23:1, n.pag.

Silverman, Marissa (2012), ‘Community Music and Social Justice: Reclaiming Love’, in G. E. McPherson and G. F. Welch (eds), The Oxford handbook of music education, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 155–167.

Tuckett, Anthony G. (2007), ‘The Meaning of Nursing-Home: “Waiting to Go up to St. Peter, OK! Waiting House, Sad but True” – An Australian Perspective’, Journal of Aging Studies, 21:2, pp. 119–13.

Turner, Kathleen (2020), ‘Critique not Criticism: why we Ask the Questions we Ask’, Transform: New Voices in Community Music, 2, pp. 4–14.

Van der Merwe, Liesl, Wentink, Catrien and Morelli, Janelise (2021), ‘Exploring Interaction Rituals during Dalcroze-Inspired Musicing at Oak Tree Care Home for the Elderly: an Ethnography’, in J. Boyce-Tillman, L. Van der Merwe and J. Morelli (eds), Ritualised belonging: Musicing and Spirituality in the South African Context, Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 43–64.

Wentink, Catrien and Van Der Merwe, Liesl (2023), ‘A Duoethnography about Musicking at an Older Adult Care Home during COVID-19’, Approaches: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Music Therapy, n.pag.

Yap, Angela Frances., Kwan, Yu Heng, Tan, Chuen, Seng Tan, Ibrahim, Syed and Ang, Seng Bin (2017), ‘Rhythm-Centred Music Making in Community Living Elderly: a Randomized Pilot Study’,BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 17:1.

Yesavage, Jerome A., Brink, T.L., Rose, Terence L., Lum, Owen, Huang, Virginia, Adey, Michael and Leirer, Von Otto (1982), ‘Development and Validation of a Geriatric Depression Screening Scale: a Preliminary Report’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17:1, pp. 37–49.